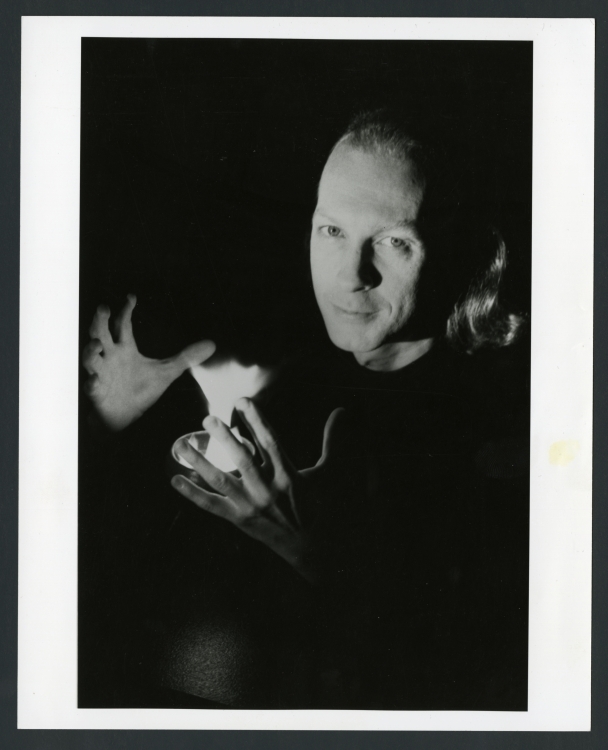

A Tribute to Creativity

About ten years ago Bill White kindly invited me to a cocktail party he was hosting downtown. There, I literally bumped into his brother Robert. The truth be told, Robert actually “got in my way” – does that sound familiar. Robert, just a little aggressive?!! I didn’t know it then – I thought this was a rather pushy individual – but I had just found a fine friend. We babbled awhile – about Barber and Bach. I have babbled with Robert about a lot of things since that time, and I want to share with you now something of what I have learned, during this friendship, about him and his life and work.

It is hardly surprising that it would be through music that one would make a connection with Robert. Robert loved baroque, and especially Bach. And he loved the great 20th century Russian composers, especially Prokoviev and Shostakovich. To lovers of music, this might seem like a huge contradiction; two discordant and seemingly incompatible styles. The fact that Robert could so easily rationalize their connection and harmony says much about the breadth of his interpretive vision, his personality and his approach to life. On the one hand, Bach’s meticulous, complex, compositional structure – multidimensional mazes of unfathomable counterpoint; and precision to the n’th degree. On the other hand, the unrestrained passion and unbridled emotional trauma of the Russian composers blazing like writhing Cossack bodies on a Balkan battlefield. They cast off the inhibitions of preceding centuries. Robert admired the courage and candor of it. This was all about “feeling”.

Robert did not believe that feelings or opinions were for hiding somewhere for the sake of social expedience or political correctness. Feelings were what humanity was all about; and feelings should be expressed and exposed. That’s what the great Russian composers of the twentieth century did with such vengeance. And Robert understood that Bach achieved the same goals, but with guile and mathematical control. Bach was like the tapestry weaver. The finer and tighter the stitch the more and more the structure became subsumed by the emotion expressed. The pattern or picture of Bach’s tapestry emerged dominant over the unbelievable complexity of his stitch-work. I personally think that in some of his major compositions Robert wanted to reconcile Bach’ism and Prokovief’ism. And I think that parts of his piano concerto, for example, manifest this.

The point of all of this is to say that there was a dominant thread that bridged Robert’s musical philosophy and guided him in his personal life. This was “the expression of feeling”.

Robert worshiped music as the highest and most expressive of all the art forms – infinitely more powerful and expressive and subtle than any of the many visual arts, the written or spoken word or dance or theatre for the expression and conveyance of feeling. I would argue with him the case for the written word, because I enjoy the reading and interpretation of poetry and other writings, but I had to concede that, while words may articulate “ideas” and “meaning” and “reasons why”, they cannot master the expression of “feeling”.

Ask brother Bill, the former mayor of our city of Houston, what it feels like to deal with the City Council over Proposition 1, and he will probably tell you about the events and circumstances and personalities and the debates and votes that make him either happy, frustrated, relieved, sad, gratified or outright pissed off. But, when Bill says “sad” could he describe what color and tone of “sad” he is talking about? Could you? Listen to Barber’s Adagio for strings and you’ll find about ten thousand different kinds of “wistful” or “sad”. Ask Bill – senior or junior – what it was like to feel the buzz, intensity and excitement of Bill’s fantastic campaign organization when he ran for Mayor, and they would probably describe many of the elements of that organization and the events that occurred. If you want to catch a piece of the “feel” of it, Robert might suggest that maybe you should listen to the score of a suitable piece of music – maybe Philip Glass’s Koyanisquatsi – which, by coincidence, Robert and I got together to listen to just a few months before he died.

For many people, and perhaps for some musicians, music is a pretty melody, or a way to tell a story, an accompaniment, a background, or an antidote to silence. Robert revered music as the ultimate medium for the expression of feelings – the innermost, deepest, most powerful and yet delicate feelings. And he knew that music could tear your soul, extravasate your gut, gently stroke an idled sentiment, prick a forgotten nerve, or light a fire in your brain. It could do it with power, pianissimo or passion, or all of the above. No other art form could come close. This conviction governed his musical mission and his life.

His musical mission was to change the world around him – the world of music – and the way it was perceived and appreciated. And his basic modus operandi, when you cut through it all, was to beseech, teach and preach to everyone he touched. He educated all of us; and he led us. We were all his pupils or protégés.

To his youngest students at the High School for the Performing Arts, he impressed on them that they already possessed the power of musical composition and expression. Just be aware of your feeling and make sound to express it. Get it out. Put it on the table. That’s music. You don’t need much grammar or vocabulary to get started.

To his performing artists he begged them to finish the composer’s work by importing and contributing their own passion and feeling to the work. Mere players need not apply. Mere “Players” are for Shakespeare’s play within the play, in Hamlet. Robert wanted you to be a serious, thinking, feeling musical performer.

To those who commissioned his work, he first would interrogate them intensively for the feelings that drove them to make their request. Robert didn’t want to compose into an empty vessel. He wanted a serious and meaningful feeling to express.

To Philistines like me and like most of the population, he had to educate us to “listen” to contemporary composition, because he believed that every generation has an obligation to memorialize its creations and enrich the culture of those who succeed them. Yes, he taught us neophytes too.

Robert was therefore a teacher to us all, as he set out to leave his mark on the world. And, to achieve this purpose, he knew that he had to provide concert settings through which there could evolve an unspoken partnership of composers, performing artists, audiences and recording technicians. These were the foundation, bricks, mortar and timber of his house; and each of these elements depended on the others to sustain meaningful life. He sought to achieve this through the Foundation of Modern Music.

His philosophical attitude towards music also spilled over to his personal and social life and his organizational style, and to essentially everything he did. In his musical avocation and in his life, I would describe his qualities with the following alliteration. He was a patient, persistent, precise, pernickety, perfervid, passionate, purposeful, perfectionist. These qualities were essential to his avocation as a composer and a pianist.

But of course, as it is with us all, our greatest strengths sometimes contribute to our weaknesses. Robert’s great strengths were not always the perfect skill-sets for the business side of his life, and it would only be fair to say that management skills like the art of delegation and supervision, financial budgeting and forward planning did not come naturally to him. When Robert knew what had to be done and he couldn’t be certain of how it would get done right, he would just put his head down and do a frontal attack on his own; with all-night sessions or whatever else it took. A person cannot do this without dedication that is beyond description. Pernickety, perfectionist to a fault. Consequently, he worked himself to the bone, and he neglected his general medical health.

If Robert had an opinion about a serious matter, he would put it on the table and defend it. He was determined and aggressive in debate and he didn’t mind exposing himself in order to attack your wrong-headed asinine point of view. Social expedience did not get in his way. Feelings were not for holding inside. In this way he could be intimidating. But he also respected the same behavior directed against him and he understood the difference between disagreement and disaffection. He never got the two things mixed up. That is one of the things that made him an extraordinarily loyal and loving friend.

In closing, I want to refer to four brief lines of verse that Robert set to music and performed in London 2002, dedicated to the memory of firefighters who fell on 9-11. This is known as “Michael’s Prayer”, and was a text carried on the person of Father Michael, a fire department chaplain, who was slain by falling debris while ministering to stricken firefighters before the second tower fell. Robert sought out and interviewed Father Michael’s closest friends so as to discover the feeling and passion that these lines represented for them and for Father Michael. Robert was deeply moved by these extraordinarily humble words, and because he is also now stricken before his time and gone to another place, these words now seem appropriate to Robert also:

Lord, take me where you want me to go.

Let me meet whom you want me to meet.

Tell me what you want me to say.

And keep me out of your way.

Robert, if you are up there, by all means stay out of the way of the Almighty, but we thank you for getting into ours.

Patrick Bromley

Houston, Texas

May 4, 2004