Residences

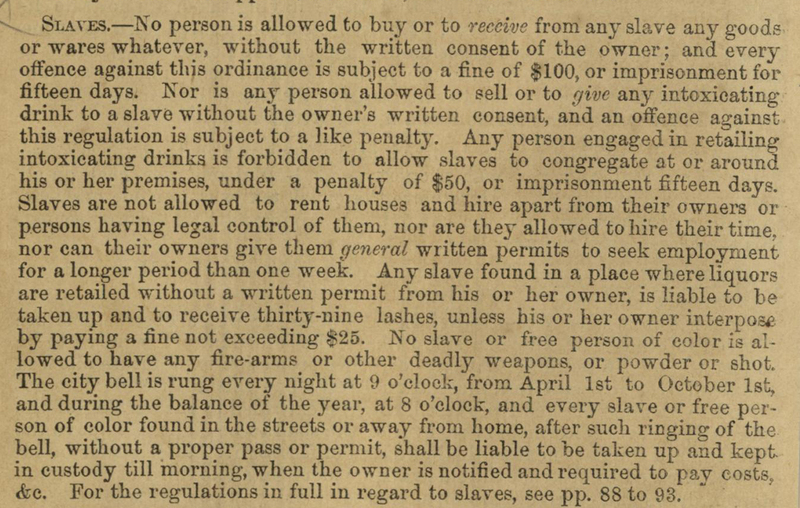

Until the 1850s, enslaved people had some opportunities to rent their own properties in Galveston's backalleys. In an editorial in The Civilian and Galveston Gazette, H. Stuart bemoaned that there were at least forty houses occupied by enslaved people by 1851.

Here's an excerpt:

"This matter has been the cause of no little trouble to the authorities and complaint by the citizens. There are upwards of forty houses in town occupied exclusively by negroes, and it is next to impossible, with the limited police of the city, to prevent occasional disorders among them."

As indicated in the final lines of Stuart's editorial, white citizens were encouraged to report any violations of these living ordinances, the maximum punishment for which was 39 lashes for the enslaved person and a $50 fine for anyone renting to the slave as well as the enslaved person's owner.1

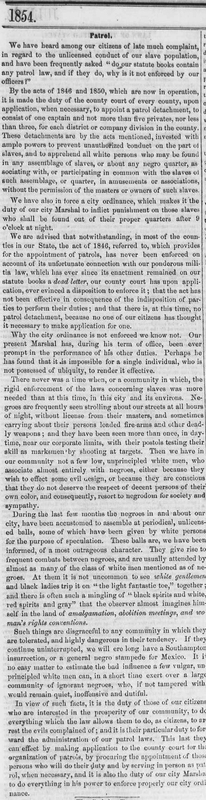

By 1854, white Galvestonians apparently became increasingly incensed by enslaved people living their lives outside of their labor obligations. Interactions between enslaved people and poor, working-class white citizens seems to have been a particularly sore point for the author. The article on the left articulates an intensified call for citizen reporting and patrolling. Here are some excerpts:

"We have heard amog our citizens of late much complaint in regard to the unlicensed conduct of our slave population, and have been frequently asked "do our stature books contain any patrol law, and if they do, why is it not enforced by our officers?

"There never was a time when, or a community in which, the rigid enforcement of the laws concerning slaves was more needed than at this time, in this city and its environs. Negroes are frequently seen strolling about our streets at all hours of night, without license from their masters, and sometimes carrying about their persons loaded fire-arms and other deadly weapons... Then we have in our community not a few low, unprincipled white men, who associate almost entirely with negroes, either because they wish to effect some evil design, or because they are conscious that they do not deserve the respect of decent persons of their own color, and consequently, resort to negrodom for society and sympathy."

![[cropped] Civilian and Galveston Gazette July 22 1851.jpg [cropped] Civilian and Galveston Gazette July 22 1851.jpg](https://digitalprojects.rice.edu/facingthegulf/files/fullsize/bc93207bd10fde38f24f4fba13af46cc.jpg)