Fortifying the Island

"Slave labor made the Confederacy function, as it had the antebellum South."1

Texas joined the Confederacy in early 1861. Galvestonians (with the right to vote) voted overwhelmingly in favor of secession 765 to 33.2

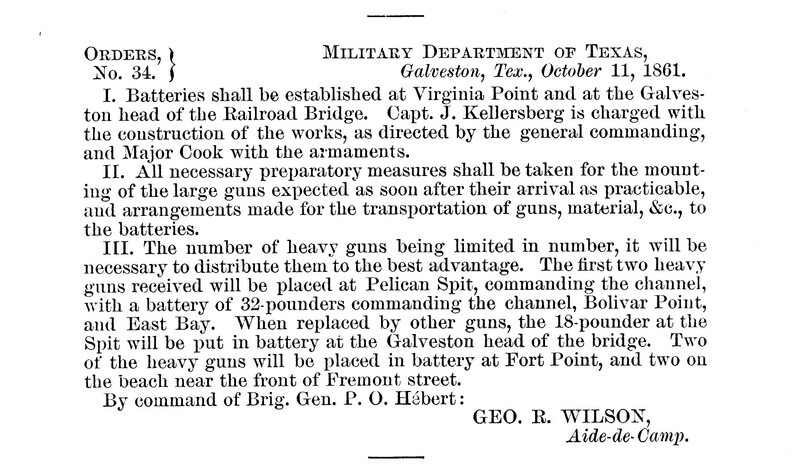

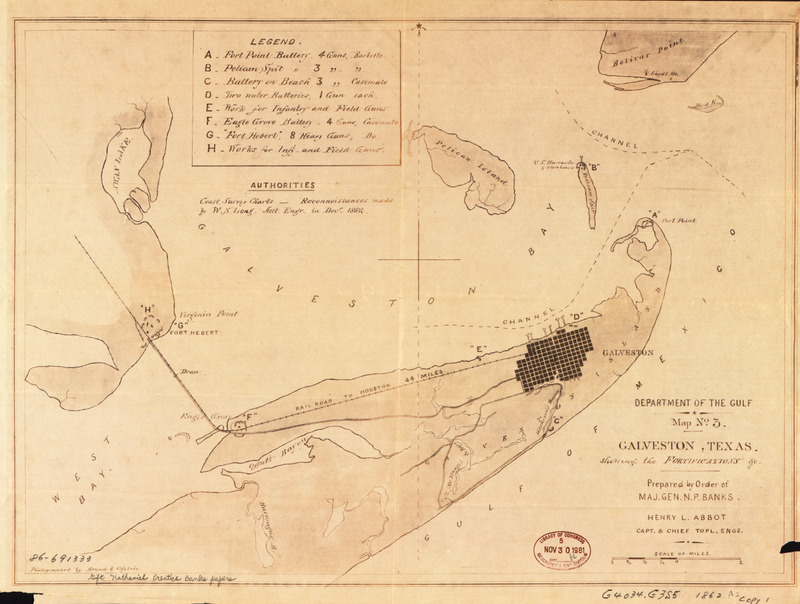

On July 2, 1861, the U.S.S. South Carolina arrived in Galveston Harbor and the Federal blockade of Texas' largest city and busiest seaport ensued. On October 11, 1861, Confederate engineer and Swiss-born Galvestonian Julius Getulius Kellersberg was assigned by Brigadier General Paul O. Hébert to lead the construction of fortifications on and around the island. See General Order No. 34 on the left to read Hébert's instructions for positioning Galveston's artillery batteries.

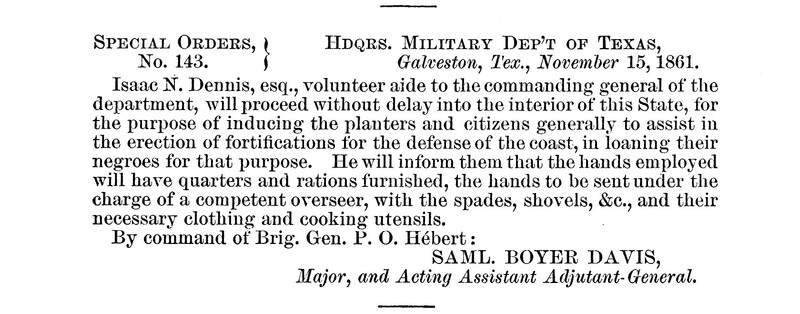

About a month later, Major Samuel Boyer Davis notified military authorities at Galveston that an agent would soon begin traveling throughout Texas to convince enslavers to "loan" bondspeople who could help build Galveston's fortifications. This act of soliciting enslaved people's labor is an example of impressment, a policy that the Confederate government used to seize not only enslaved people but also food, fuel, and other commodities for the war effort.3

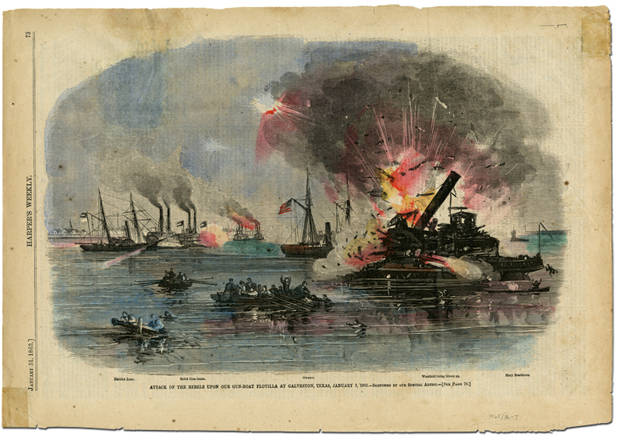

On October 4, 1862, the first Battle of Galveston took place as Confederate Colonel Joseph J. Cook declined Union Commander William B. Renshaw's demands for surrender. After Renshaw's naval forces quickly incapacitated Confederate artillery, Confederate and Union forces agreed to a four-day truce after Union Commander William B. Renshaw threatened to shell the island. All remaining Galvestonians were evacuated during the truce period, and the U.S. flag was raised over the old U.S. Customs House.

The Union victory did not last long, however. In the early hours of January 1, 1863, Confederate forces led by Major General John Magruder staged a successful attack against the occupying Union forces. Almost no Union solider was left alive as Maj. Gen. Magruder recaptured the island for the Confederacy.4

In the aftermath of the victory, Gen. Magruder was determined to prevent another Union attack and ordered Galveston's fortifications to be rebuilt. Impressment of enslaved people increased, partly due to the Confederate government making impressment an official legislative policy in March 1863.5

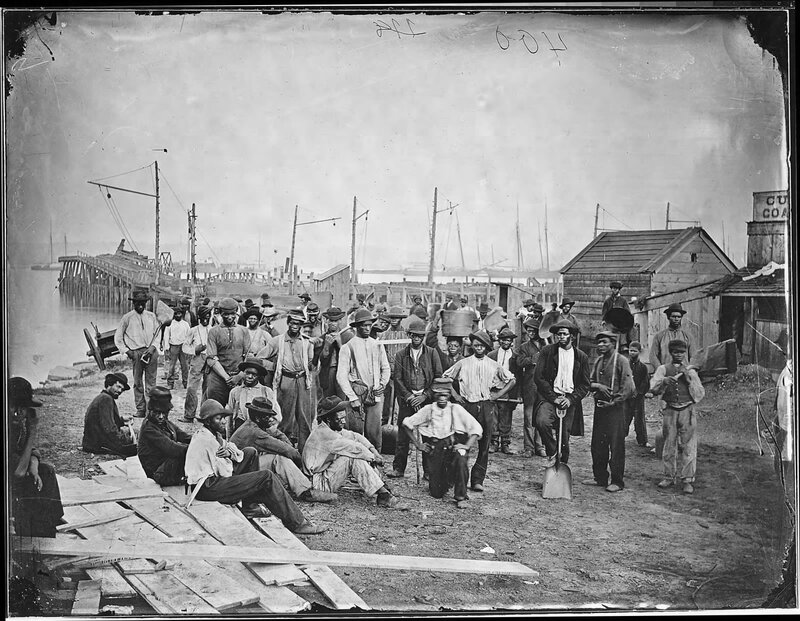

Across the South, impressment generated tension between enslavers who did not want their human property taken and commanders like Magruder who felt enslaved people's labor were their most valuable asset in completing necessary military work. White Confederate troops felt that they were above doing the hard manual labor of digging trenches and putting up sandbags in order to fortify towns, so enslaved people were recruited by the thousands to do so instead.

Many enslavers refused to send their bondspeople into service, though many more ultimately complied; "their grumblings about impressment were similar to privates' gripes about conscription: they did not always like the undemocratic nature of the army, but they feared that defeat and abolition would be far worse."6

Military authorities emphasized patriotism and civic duty in order to persuade enslavers to hire out bondspeople. Avoiding impressment was considered cowardly, as one editor of Houston's Weekly Telegraph implies in an editorial published on January 14, 1863. Click on the editorial, pictured on the left, to read the full transcription. Here are a few excerpts:

"We regret to say that slave owners are not responding to the call of Gen. Magruder for negroes with that alacrity which the emergency of the case demands. It is little to the credit of our people that such a call should have to be made twice upon them...

We said before that Gen. Magruder did not like to impress negroes. He does not wish to send a file of soldiers with bayonets on the plantations to take what ought to be freely freely offered. But if the called for labor does not come, this course must and will be pursued. Galveston Island he says shall be defended. The enemy shall be kept off the soil of Texas while he is on it if possible, and if any of the people of the State are not willing to help him, they shall be made to help him...

Planters, make a virtue of necessity, and hurry your negroes in. Nine tenths of you, we know, are ready and willing, but are delaying without cause. Don't delay an hour longer.

Let no time be lost and we will have the beautiful Island City in a condition to fight off all the hosts of Lincolndom, should they see fit to come against it."

Below are two examples of Confederate citizens records that show receipts for enslaved people who were impressed into service at Galveston. Roll over different areas of each document to read transcriptions and further information.

In his memoirs about his time in the Confederate Army, Kellersberger recalls the vast number of enslaved people who were brought under his command via impressment:

"The battle of Galveston on January 1, 1863, put us back into possession of the port and city from which we had been driven on September 15, 1862. Unfortunately, this battle had no halting effect upon the progress of the war; however, it did result in the fortification of the entire Texas coast, thus protecting Texas from much of the war’s fury. Our General, an energetic officer, gave an order to fortify the entire island as he had been assured that he would be sent twenty heavy cannon from the city of Richmond. We had approximately 5,000 negroes at our disposal and a corps of 300 good and dependent German craftsmen, who knew that so long as they stayed with me there was no danger that they would be sent to the front. I was Major and Chief of the Engineering Corps of the State of Texas at that time..."7

One of the reasons enslaved people were so heavily relied on was that they were considered more expendable and less valuable than white soldiers by military authorities. Philles Thomas, a formerly enslaved woman interviewed by the Works Progress Administration in the 1930s, was too young during the Civil War to remember its events. However, Philles's mother told her later that her father was killed while assisting with Galveston's fortifications:

"I can't 'member my daddy, but mammy told me him am sent to de 'Federate Army and am kilt in Galveston. She say dey puttin' up breastworks and de Yanks am shootin' from de ships. Well, daddy am watchin' de balls comin' from dem guns, fallin' round dere, and a car come down de track loaded with rocks and hit him. Dat car kilt him."8

![[cropped] Impressment call_Weekly Telegraph.png [cropped] Impressment call_Weekly Telegraph.png](https://digitalprojects.rice.edu/facingthegulf/files/fullsize/00ccadeb29110a83f02607599707f6ed.jpg)