U.S. Coastwise Trade

As demand for sugar and cotton increased in industrial Europe and the northeastern United States at the turn of the 19th century, plantation agriculture rapidly expanded into the south and southwest peripheries of the U.S. With this expansion came a heightened demand for enslaved labor, and since the ratification of the 1808 Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves, American enslavers and traders were legally limited to the population of enslaved people already on U.S. soil. Today, the domestic trade and forced migration of approximately one million enslaved people from the upper South to the lower South is known as the Second Middle Passage.

Once enslaved people were sold or brought along with those who claimed them as property when they moved, bondspeople were often forced to make the trek across state lines on foot or in carriages. The image of people walking in single file in shackles is often conjured when thinking about the Second Middle Passage. However, a less recognized facet of this chapter in the African American diaspora is the U.S. coastwise slave trade, which refers to the exchange of enslaved people within the continental U.S. along its southern and southeastern coastlines.

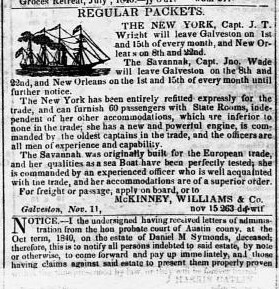

Galveston Bay was one of the busiest ports in the U.S. for coastwise trade not only of enslaved people but also everyday merchandise and commodities. Shipping was regularly advertised in Texas newspapers like the one featured below, a Galveston publication titled The Semi-Weekly Journal. Zoom into the upper right corner of the newspaper below to see advertisements for several steamships offering freight and passage between Galveston and various cities. Since enslaved people were considered chattel property, their passage was considered to be freight.

One of the steamships, the Palmetto, had arrived in Galveston on May 10, 1850, four days before the publication of this issue. In the second column of the page near the bottom, a small article titled "Passengers per Steamship Palmetto" reported that the Palmetto had arrived with six enslaved people on board.

This particular newspaper issue also offers many more details about the daily business activities that regularly shaped the lives of enslaved people in Galveston.

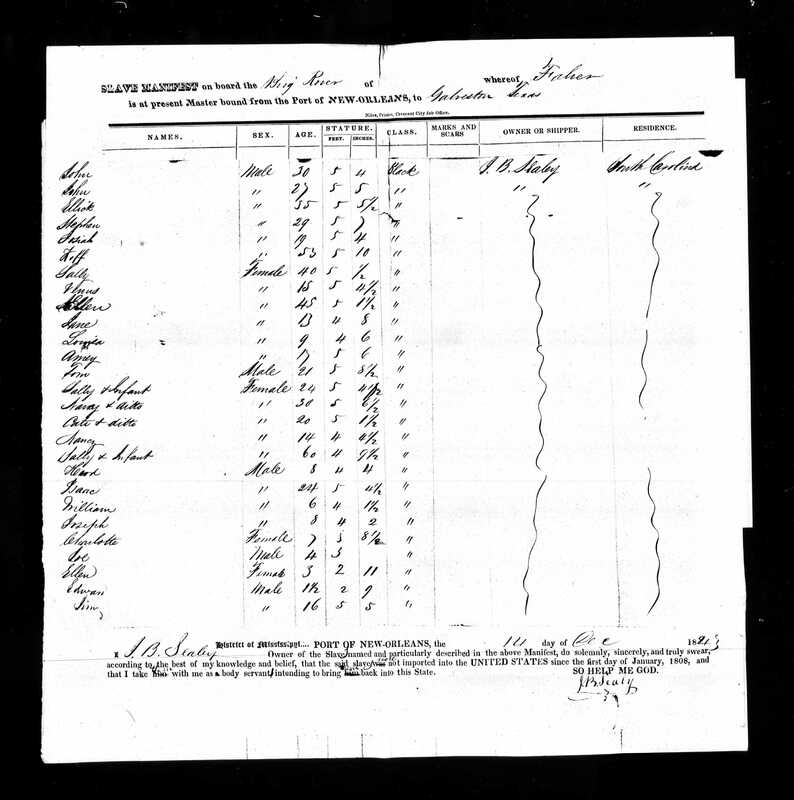

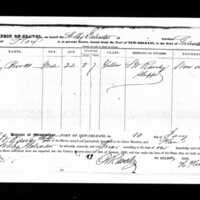

For each voyage of every vessel that transported enslaved people within the U.S., the captains were required to file a manifest of enslaved people in their cargo with a collector of customs. Roll over the image below to see the various details of domestic slaving vessels that were usually recorded.

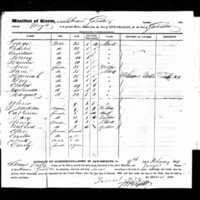

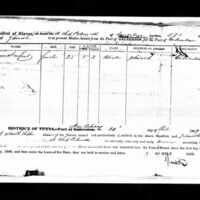

The gallery to the left contains 7 manifests listing enslaved people who were transported on coastwise voyages from New Orleans to Galveston. Some of these manifests document the passage of only one or two enslaved people, while others list several dozen people. Click on each document to read a transcription of the bondspeople listed.

Please keep in mind that these documents only represent a couple hundred out of thousands of enslaved people who disembarked in Galveston -- the total number of whom is still not known.

The first manifest at the top of the gallery lists 31 enslaved people who were boarded onto a brig named Rover, which was captained by someone named Faher. They embarked from New Orleans to Galveston on December 14, 1843, and were claimed as porpoerty by a J.B. Sealey of South Carolina. Below is a transcription of the names of bondspeople listed on the manifest:

John, a 30 year old Black man who stood 5' 4" tall

John, a 27 year old Black man who stood 5' 5" tall

Ellick, a 35 year old Black man who stood 5' 5.5" tall

Stephen, a 29 year old Black man who stood 5' 7" tall

Josiah, a 19 year old Black man who stood 5' 4" tall

Koff, a 55 year old Black man who stood 5' 10" tall

Sally, a 40 year old Black woman who stood 5' 0.5" tall

Venus, a 15 year old Black girl who stood 5' 4.5" tall

Ellen, a 45 year old Black woman who stood 5' 1.5" tall

Jane, a 13 year old Black girl who stood 4' 8" tall

Louisa, a 9 year old Black girl who stood 4' 6" tall

Amey, a 17 year old Black girl who stood 5' 6" tall

Tom, a 21 year old Black man who stood 5' 8.5" tall

Sally, a 24 year old Black woman who stood 5' 4.5" tall

Sally's infant

Nancy, a 30 year old Black woman who stood 5' 6.5" tall

Nancy's infant

Cate, a 20 year old Black woman who stood 5' 1.5" tall

Cate's infant

Nancy, a 14 year old Black girl who stood 4' 4.5" tall

Sally, a 60 year old Black woman who stood 4' 9.5" tall

Sally's infant

Hank, an 8 year old Black boy who stood 4' 4" tall

Isaac, a 24 year old Black man who stood 5' 4.5" tall

William, a 6 year old Black boy who stood 4' 1.5" tall

Joseph, an 8 year old Black boy who stood 4' 2" tall

Charlotte, a 7 year old Black girl who stood 3' 8.5" tall

Joe, a 4 year old Black boy who stood 3' tall

Ellen, a 3 year old Black girl who stood 2' 11" tall

Edward, an 18 month old Black boy who stood 2' 9" tall

Jim, a 16 year old Black boy who stood 5' 5" tall

Where can I find out more about enslaved people who disembarked at Galveston?

Student and faculty researchers at Rice University are currently documenting all known ship manifests of enslaved people embarking and disembarking at Texas ports. These ports include not only Galveston, but also Matagorda Bay, Velasco, Port Lavaca and others. In 2022, data from these manifests will be available in the Intra-American Slave Voyages Database, an online research tool that compiles data on slaving vessels from across the Atlantic world into a searchable database.