Smuggling in the 1830s

Most histories of American slavery will note the 1808 Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves as the end of enslaved people's capture directly from Africa, since that law stated that enslaved people could no longer be brought into the U.S. from any other country. However, Texas was not subject to any U.S. laws at that time -- in fact, it would not become a U.S. state for another 37 years.

Smuggling enslaved people from Cuba was prompted by a combination of factors. First, Anglo colonists in Texas -- also known as "Texians" were angry about the young Mexican Republic's legislative actions against slavery throughout the 1820s. By the time 1830 rolled around, the Mexican government not only wanted slavery to end, but also wanted to halt the huge waves of Anglo immigrants altogether. The timeline below briefly goes over Mexico's position on slavery from 1821-1830.

In response to tightening restrictions on slavery in Texas, some Texian plantation owners began look elsewhere for depots of enslaved people who could plant and harvest their expansive Brazoria, Matagorda, and Fort Bend plantations. Cuba became the destination of choice for these "blackbirders" -- enslavers and traders who engaged in the illicit traffic.

One of the most notorious smugglers of this time was Monroe Edwards, a Kentucky native who came to Texas in the 1820s to serve as an apprentice of James Morgan, a prominent businessman who would later become a commander at Galveston during the Texas Revolution. Before he established himself in Texas, Edwards participated in an expedition to Africa in 1832. Whether he personally purchased any captives from this voyage is unknown, however he made a substantial profits through the sale of those captives which he then used to purchase a plantation on the San Bernard River in the fall of 1833. The plantation had formerly belonged to Benjamin Fort Smith, who had named it Point Pleasant Plantation. Edwards renamed it Chenango, a name that would stick with the place until present day. Due to Edwards' smuggling activities, Chenango had over 100 enslaved African-born people living and working on its grounds during the 1830s.1

Edwards erected a" slave mart" at Edwards Point, near present-day San Leon on the north side of Galveston Bay. On one occasion, Africans were seen in the general area of this mart being driven by Major Benjamin Fort Smith, who also participated in the illicit trade.

Edwards' career as a trader/smuggler in Texas ended abruptly in 1837 when his various schemes of forgery and swindling finally caught up with him (Robbins 158).

In 1836, Nicholas P. Trist, the U.S. consul at Havana, estimated total departures of Africans to Texas at a thousand. In 1843, British Consul William Kennedy at Galveston estimated that between 1826 and 1836, total imports of enslaved African people to be 504, with approximately three hundred of those brought in by lower Brazos traders.2

We may never be able to know the precise number of Afircan-born captives who were brought to Texas from Cuba. However, we do know of a few notable voyages based on the alarm they caused Texas and U.S. officials.

Click through the map below to read more about how, when and where African-born bondspeople were smuggled from Cuba into Texas. While most of these "blackbirders" were Brazoria plantation owners and enslavers, Galveston Bay still played a role as it was an entry point for these clandestine voyages.

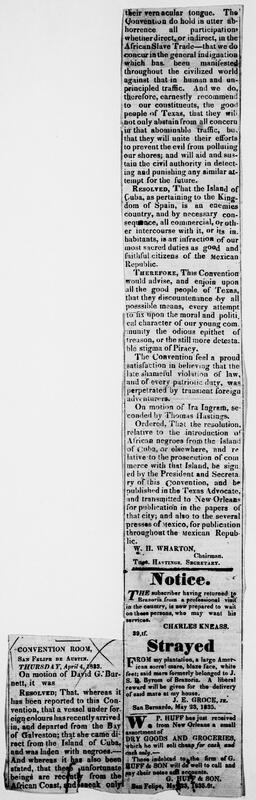

Delegates at the Convention of 1833 apparently took the issue of continued importation of Africans seriously. They not only publicly acknowledged the arrival of a vessel carrying enslaved people in Galveston Bay during the convention itself, they also asked that the article on the right be published for Texians themselves to read.

Here are some excerpts:

"Whereas it has been reported to this Convention, that a vessel under foreign colours has recently arrived in, and departed from the Bay of Galveston; that she came direct from the Island of Cuba, and was laden with negroes. And whereas it has also been stated, that these unfortunate beings are recently from the African Coast, and speak only their vernacular tongue.

"The Convention do hold in utter abhorrence all participation whether direct, or indirect, in the African Slave Trade--that we do concur in the genreal indignation which has been manifested throughout the civillized world against that in human and unprincipled traffic. And we do, therefore, earnestly recommend to our constituents, the good people of Texas, that they will not only abstain from all concern in that abominable traffic, but that they will unite their efforts to prevent the evil from polluting our shores; and will aid and sustain the civil authority in detecting and punishing any similar attempt for the future.

"This Convention would advise, and enjoin upon all the good people of Texas, that they discountenance by all possible means, every attempt to fix upon the moral and political character of our young community the odious epithet of treason, or the still more detestable stigma of Piracy."

Although the delegates seemed adamant about denouncing the smuggling, they were reluctant on placing blame on colonists:

"The Convention feel a proud satisfaction in believing that the late shameful violation of law, and of every patriotic duty, was perpetrated by transient foreign adventurers."

The first Congress of the Republic of Texas took up the issue of smuggling and made it a capital crime to bring African-born captives from Cuba into Texas. With this law in place, the risks of smuggling drastically increased and likely deterred Texas enslavers from engaging in what Sam Houston called an "unholy and cruel traffic."3

Use the viewer below to read this important piece of legislation, titled "An Act Supplementary to an act for the punishment of Crimes and Misdemeanors," enacted on December 21, 1836:

This period of trafficking had a significant and lasting impact on the population of African-born people in Texas. These illegal importations prove that even though Texas never participated directly (i.e. legally) in the African trade as the eastern U.S. states did in the 17th and 18th centuries, Brazoria and surrounding counties became home to a large African community.

In his article "Blackbirders and Bozales: African-Born Slaves on the Lower Brazos River of Texas in the Nineteenth Century," historian Sean Kelley wrote:

"The 1870 census, notorious for its undercounting, enumerated 120 African-born men and women in Brazoria County. Virtually all were fifty and older, a fact that supports the notion that almost all importations occurred within a relatively narrow window in the 1830s. It also suggests an 1830s population several times that size, possibly approaching a thousand. In sum, it seems reasonable to suggest that the African population of Brazoria County approached the higher end of the five hundred–to–one thousand range, and possibly even exceeded it."4