Birth and Death

Introduction

Several of the letter writers compare death to birth as a way of helping Mrs. Kaderli’s 10-year old daughter to cope with her fear of death. The comparison is clarifying because it centers on the question of oblivion: the nothingness that precedes birth is equated to the nothingness that follows death. This is comforting because birth, for the child, is the opposite of the terror of death. However, it has been observed that the comparison is inapt: the two states of oblivion are not the same for the individual. While the fear of nothingness itself is often regarded as the origin of our fear of death, this conclusion seems to obscure certain other, more fundamental fears. Both of these uses and shortcomings of presenting birth as a symmetrical bookend to death come out in the letters of several writers in the Kaderli collection.

Alan Watts

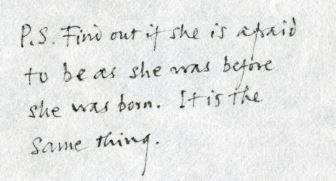

After communicating his regrets at not being able to say more, Alan Watts closes his short letter by asking a curious question: “P.S. Find out if she is afraid to be as she was before she was born. It is the same thing.” This may seem like a rather flip response to a deep question, but it actually opens up on a long-running debate over the nature of death that has been treated by ancient and modern philosophers alike. Specifically, it is a reiteration of the second Epicurean argument against the fear of death, called the “Symmetry Argument,” communicated by Epicurean poet Lucretius (“On the Nature of Things," bk 3). He suggests looking back on the infinite non-existence prior to birth and how we do not fear it. This pre-natal existence mirrors our post-mortem experience, and thus, equally, our post-mortem experience should not be feared. Intuitively, this comparison seems plausible. However, several philosophers have responded to this classic Epicurean argument by considering potential asymmetries. While the superficial condition of non-existence may (hypothetically) be the same before birth and in death, it is the relation of this non-existence to our lives that grants its significance.

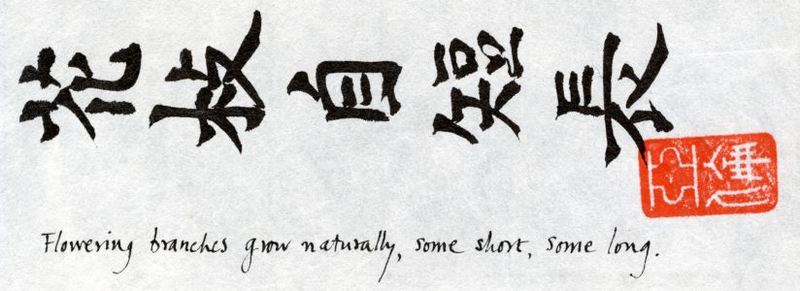

In his paper titled, “Death,” Nagel elaborates on this idea with what he calls the “Deprivation Argument.” First, he establishes that death is not necessarily “bad” in a positive way, but rather because it deprives us of what we consider to be “good,” which is life. Although, even this premise can be called into question; Alan Watts was a British philosopher who popularized Eastern philosophy for a Western audience, and, along with his letter, he includes a popular zen poem: “Flowing branches grow naturally, some short, some long.” In the full, original poem, the preceding phrase is: “In the landscape of spring, there is neither better, nor worse.” Therefore, Watts is suggesting that neither a “long” nor a “short” life can be compared to each other in terms of goodness and value. It is simply the way of life, and as flowering branches naturally grow long or short, so are both lives equally natural and beautiful.

However, Nagel’s first premise, regardless of its ultimate validity, does reveal a common understanding of life and death. That is, "life" is good, and "death" is bad because it takes life away from us. We can continue with this idea in order to elucidate the origin of our fear of death and the validity of the symmetry argument. Nagel writes that we can grant that death deprives one of life and that without death we would continue to go on living; conversely, it does not make sense to say that the time before birth is time that we are deprived of by our subsequent birth—for we have never lived prior. Therefore, the temporal relationship of this non-existence reveals the apparent asymmetry between birth and death. We have nothing that is lost in the time before our birth (and there would be no person to assign this loss to, for we do not yet exist), while we have everything in life to lose in death. Therefore, this reveals that we do not necessarily fear death for its mere, superficial aspect of non-existence, but rather non-existence when the alternative is the continuation of life. This is a distinction that cannot be assigned to the experience of birth and the time preceding it, and thus, in the context of our fear of death, the time before birth is not the same as the time after our death.

Graham Greene

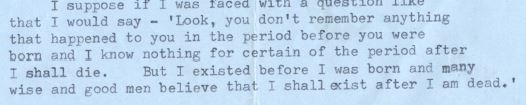

In his letter to Mrs. Kaderli, Graham Greene also speaks of the parallel between birth and death, but he has a slightly different approach that appears to take on an opposite meaning from the original Symmetry Argument by Epicurus. Greene writes, “Look, you don’t remember anything that happened to you in the period before you were born and I know nothing for certain of the period after I shall die." Interestingly, the symmetry between these two time periods that he speaks of is not affirmatively one of non-existence; while he doesn’t say anything conclusively, the symmetry he appeals to is the mystery of our existence before birth and after death. This mystery, like oblivion, is considered to be another basis for our fear of death. In this first sentence, he utilizes the symmetry argument to quell fears stemming from the mysterious and unknown aspect of death, of not knowing what will come next, by appealing to the fact that we know nothing of what our experience was prior to birth. He goes on to say, “But I existed before I was born and many good and wise men believe that I shall exist after I am dead.” In other words, Greene appears to be endorsing a kind of immortality, an immortality that he doesn’t know much about but that parallels the infinite existence that stretched prior to our birth. He uses the symmetry argument not to quiet our fears surrounding the “experience” of non-existence, but rather the opposite: to point to a kind of positive immortality that bookends our lives.