Creation/Procreation

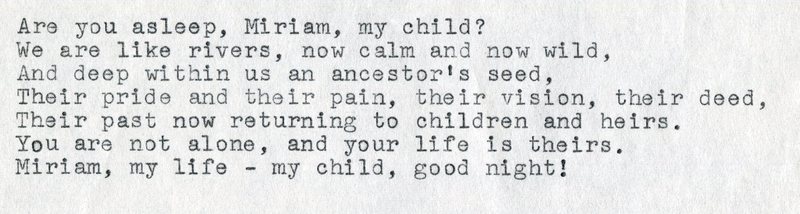

In the letters of the Kaderli collection, creation, in both a physical and abstract sense, is posed as a mechanism of immortality. An example of physical creation, or procreation, is the notion that one is immortalized physically through the lives of her descendants. In a poem shared by Theodor Reik in his letter, this direct continuation of the lives of ancestors is symbolized as the “ancestor’s seed.”

“And deep within us an ancestor’s seed,

Their pride and their pain, their vision, their dead,

Their past now returning to children and heirs.

You are not alone, and your life is theirs.”

Instead of the spiritual continuation of people through memories and ideas, the metaphor of a physical “seed” conveys the notion that the ancestor’s lives are made immortal in a more direct, physical sense. It is as if the ancestors of people live vicariously through their descendants, and in this way are given life beyond death. Nelson Glueck also speaks about the immortality of procreation, comparing the cyclicality of human lives to the birth and death, appearance and reappearance, of leaves and flowers in nature: “There is a definite immortality in the fact that you in your person preserve the identity of your parents even as your daughter some day when she has children will preserve the identity of her parents, and so on.”

Furthermore, Leonard Bernstein lists several means of immortality, some shared with other writers, such as reproduction, relationships, and understanding. Notably, though, he is unique in mentioning art among these. It is the creation of art, ideas, philosophical theory in the search for truth, etc., which characterizes the abstract notion of creation as a mechanism of immortality. Plato, an ancient Greek philosopher, terms these types of creative works “spiritual progeny” which attempt to carry on the “being” of the subject (Dillon, 1981).

However, regardless of the nature of the creation, it is the fear of death and subsequent desire for immortality that encourages one to engender things of value. It is this type of creation, the “creation of all worldly beauty and value,” that “expresses the creator's own identity, and in which she can, in a specifically human way, live on in the world after her death” (Nussbaum, 1989).