Religion and Death

In the letters, many writers appealed to a religious faith, through trust in God and love for God [See section Immortality— Religious Immortality], to construct their beliefs in immortality and the afterlife.

Interestingly, this religious rhetoric, as well as a kind of doubt, is expressed in the letter from C.S Lewis, who is often known for his religious texts such as the children’s series, The Chronicles of Narnia”. On the outward face, C.S Lewis gives expected advice: “There is of course the New Testament. Can’t you and she read the Gospels together?” In the body of his letter, C. S. Lewis gives Mrs. Kaderli many resources to read alone and with her daughter to find answers to her questions on death, primarily in religious texts. The overall message is one of religious compliance and could best be associated with a belief that the problem of death is best left for God.

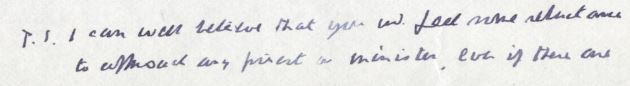

However, the postscript of the letter follows a different line. In the first part of the postscript, C.S Lewis notes: “I can well believe that you would feel more reluctant to approach any priest or minister, even if there are any good ones within reach. But remember neither you nor she is going to get any assurance about having a life after death unless you accept to go along with it a good deal, which may be less welcome.” C.S Lewis suggests that in order to be assured of a life after death, one must believe in religion. Furthermore, the foundation of this faith is somewhat equivocal, as he says they must “accept to go along with it a good deal.” This sentiment, much more detached than one would expect from a theologian, is a remnant of prior experiences. The Kaderli letter was written by C.S Lewis in 1962. Prior to this, C.S. Lewis had written a book, "A Grief Observed," which showed his turmoil with faith in the context of his wife’s death.

“A Grief Observed” was compiled from writings Lewis left in journals after the passing of his wife due to cancer and shows a testing of Lewis’s faith. Amid this uncertainty, Lewis asserts that it is possible that a God who would inflict pain upon the living could also do the same on the dead. This would then lead to the thought that God is not a kind and loving god, but instead a vengeful and sadistic being that tortures humanity in the present and the afterlife (pg. 27). In addition to the possibility of an evil God, Lewis also remarks that there may not be a God; he notes that “if God’s goodness is inconsistent with hurting us, then either God is not good or there is no God” (pg. 25). This nebulous nature of God adds uncertainty to the faithful opinions of many of the responders to Mrs. Kaderli. If there is a possibility of a nonexistent or maleficent deity ruling over us, can invoking religion be a comfort for the girl who fears death?

A similar turmoil to the one C.S Lewis experiences is present in Leo Tolstoy’s “My Confession.” Similar to C.S Lewis’ suggestion, in this raw and impassioned text, Tolstoy seems to be reasoning himself towards believing in God and religion in order to have access to the comforts and sense of meaning that religion provides for its followers. Insofar as science tells us that we are an “accidentally coherent globule of something” that is “fermenting, and will eventually fall to pieces and all questions will come to an end,” science cannot give us any answers as to the meaning of our life. Because of this, Tolstoy desperately turns to faith. His inner turmoil and newfound appraisal lead him to the conclusion that every answer from faith “gives to the finite existence of man a sense of the infinite.” He continues, “If he does not see the phantasm of the finite, he believes in that finite; if he believes in the phantasm of the finite, he must believe in the infinite.” Essentially, Tolstoy finds that science cannot give any comfort of immortality; consequently, if one wants to believe in anything eternal, he must believe in the “phantasm” of faith, of what is not seen in this finite existence.

While Lewis eventually restored his faith, he, like Tolstoy, demonstrates through his narrated crises, the comforting role that faith provides in the notion of immortality and the afterlife. By invoking religion as necessary if one wants to believe in life after death, even if not wholeheartedly endorsed, in some sense they regard religion as a means to an end.