Education

In Eisenhower’s 1955 State of the Union address, he stated that “it is the right of every American, from childhood on, to have access to knowledge” and “without impairing in any way the responsibilities of our states, our localities, communities or families, the federal government should serve as an effective agent in dealing with this problem.”1 Although education had always important to the administration and federal aid was expected, the Eisenhower administration had no preconceived notions about how to go about education policy. Before the framing for education policy as a crisis in 1955, the administration had been overwhelmed with the nation’s public health and social security. Oveta was highly committed to expanding education for children across America. Like Eisenhower, she wanted to expand education in a way in which the federal government would give the reins to the local communities first and foremost.

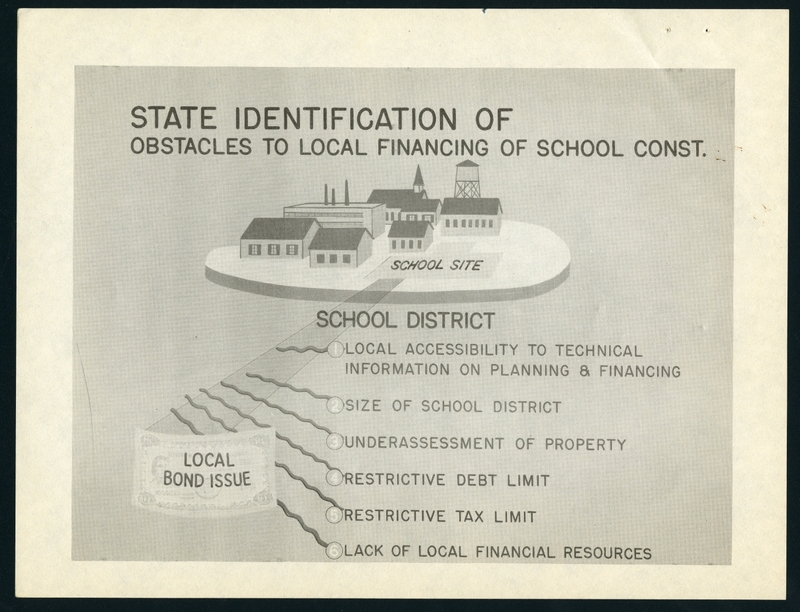

Before she suggested legislation, as always, her first step was to thoroughly research the problem because she believed that thorough research was the first step in running a bureaucratic government agency and to best inform the President (Figure 1). There were many education conferences before, but she organized the first White House conference on Education. With a Republican administration and Democratic Congress, Oveta worked hard to compromise hers and Eisenhower’s self-governance perspective with the Democratic push for more federal aid. From that conference and hard work, Oveta proposed a three-year emergency plan to build $7 billion worth of schools.2 Hobby was against just giving states school construction grants in 1953 to 1954. She argued that the local communities would just wait around for federal funding. The administration’s approach to this problem was most likely influenced by their ideology of resistance to federal intervention and falling back on the conservative rhetoric by pushing for self-reliance. To compromise with a Democratic Congress, Hobby proposed financing program for federal purchase of school bonds to encourage school construction as well as state fund matching programs with federal funds.3

At this time, the Brown v. Board of Education of 1954 case was brought to Oveta’s attention. The decision would affect the access some schools would have to funding from the federal government. While the government ended racial segregation of all schools on military reserves by the end of 1955, there was a lot of pushback from senators and Congressmen from Southern states who were proponents of segregation. As a result, the administration and the department moved slowly on desegregating other schools. The administration did not have a good response to the Southern segregationists. The backlash from the Southern states as well as Hobby’s conservative view on federal intervention allowed her to take a hands-off approach and general disinvestment on integrating in terms of school building by creating matching funds programs and emphasizing the need for communities to be self-governing.

In taking over the Children’s Bureau as well, Hobby, through her research, also determined that juvenile delinquency had significantly increased.4Through her research and ideological view on responsibility, Hobby proposed many programs and recommendations for schools to control their juvenile delinquency population. Through these efforts, she also placed emphasis on developing the state programs in mental health.