Education Implementations

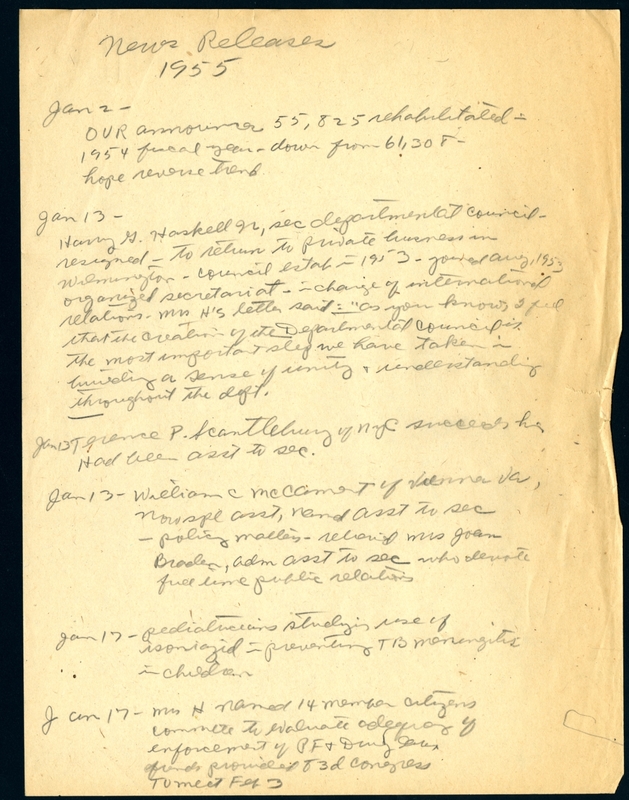

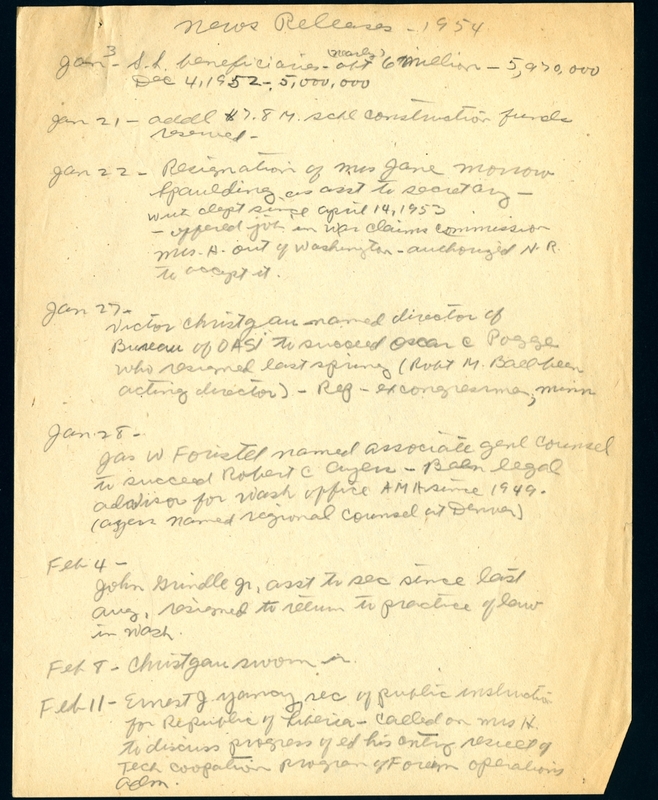

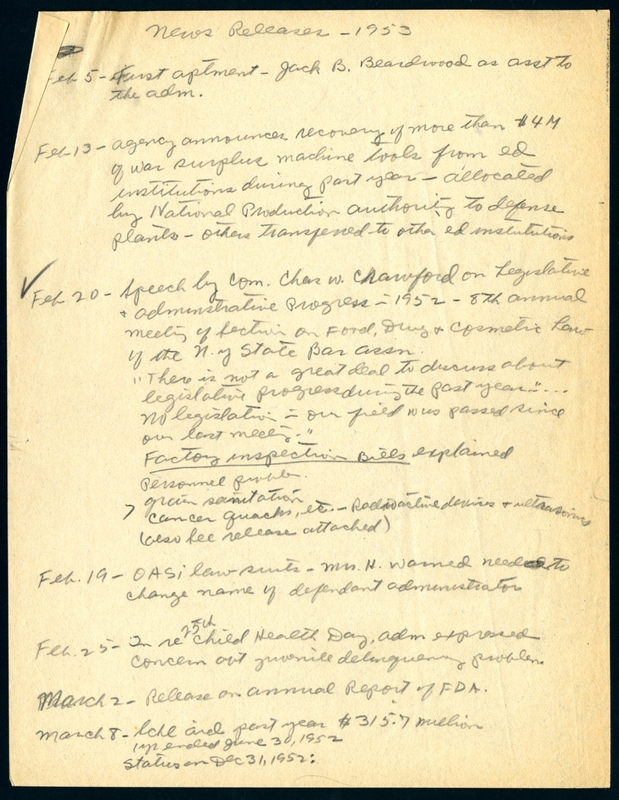

Hobby’s role in the classroom deficit was to gather all the relevant facts associated with the problem and that “the federal government should act only if it was established that the state and local governments could not handle the problem” (Figure 1, 2, 3).1 She organized the first White House conference to gather information about problems the schools were facing. Hobby’s research found that the classroom deficit was so large that unless there was a considerable increase in taxes or federal debt, the problem could not be solved. Thus, state participation, based in Hobby’s understanding of the problem, was paramount.

As the Democratic party took over Congress, a school reconstruction bill was going to be inevitable. The entire department, under Hobby’s direction, proposed legislation after close consultation with educational and school fiscal experts.2 Her requirements for an acceptable legislation included building classrooms in large numbers, building them quickly, being flexible to meet the 63,000 school districts in 48 states, and safeguarding state and local responsibility for education.3 Through research, Hobby determined that the average cost of a new classroom was $30,000.4 To further guarantee states as the primary stakeholders, instead of a priority list for federal aid grants, Hobby proposed states to put up matching funds to the federal government and the school districts would have to demonstrate inability to finance its buildings.5

In the 1953-1954 fiscal year, the department spent $197 million on federally affected school districts and $25.8 million in grants for vocational education and $5 million in grants for land-grant colleges. These grants kept on growing under Secretary Hobby’s watch to meet the growing need of education in America. By 1955, as of her retirement, the department had allocated around a half billion dollars to the Office of Education.6

Hobby’s focus in the education realm was on congressional authorization for a research program that would look into conservation and development of education for mentally retarded and gifted students, prevention of juvenile delinquency, school construction, and educational implications of technology. Hobby also used federal grants to help states to develop juvenile delinquency programs. Everyone had agreed that the number of juvenile delinquency problems had escalated during the Korean War era and afterwards. However, there was disagreement on how to go about solving the problem.7 As the leader of the Children’s Bureau, in charge of the delinquency issue, Hobby supported education of parents to understand the growth processes of childhood and “‘develop the emotional and mental strength required to live happy, useful and satisfactory lives.’”8 Through Hobby’s recommendations, many proposals were considered including training police officers trained in juvenile work in communities, building good detention facilities and services, adding expert physical and psychological examinations before courts decide a ruling for the child, staffing the courts with social services, training schools to deal with juvenile delinquents and mental health issues, and building at least one institution in each state for emotionally disturbed children.