Health

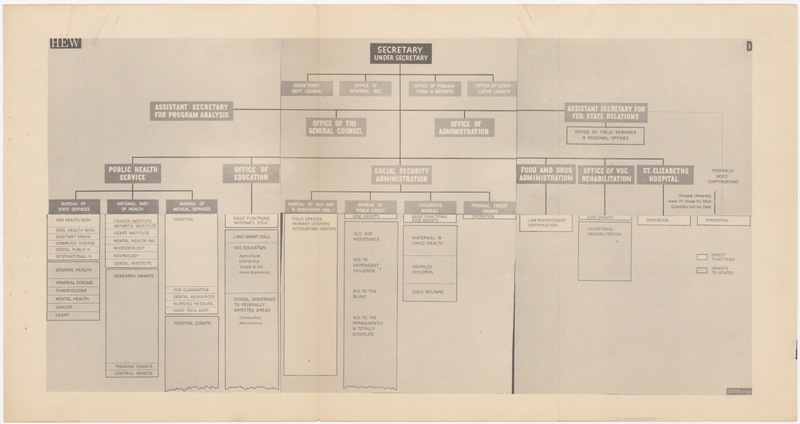

Spinks provides a broad view of how the administration linked health and dignity, “A conviction shared by most Americans as a corollary to their belief in the worth of human life and the dignity of the individual is that everyone has a right to good health and adequate medical care.”1 In a 1954 message to Congress, Eisenhower narrows his view, identifying health and dignity as being linked specifically by independence: “‘for only as our citizens enjoy good physical and mental health can they win for themselves the satisfaction of a fully productive, useful life.’”2 Hobby and her team worked to fulfill Eisenhower’s goals of realizing a healthy, productive society according to his ideology of self-sufficiency being tied to dignity which was informed by his 1950s worldview of self-sufficiency being the basis of a republic made of free and healthy citizens (Figure 1). Eisenhower’s links between health, self-sufficiency, and dignity, can be seen in his 12 proposed goals to Congress. One of Hobby’s focuses, very much in line with the ideology of independence, was on the reinsurance plan, which was a plan to increase access to “voluntary health insurance” or private market-based health insurance by funding carriers and encouraging them to provide more benefits to customers. In Hobby's dedication to public health, she realizes that health has gotten more complex from external factors, and thus also pushes for legislation for topics such as water sanitation.3 Hobby also focused beyond the individual on public health research and the distribution of polio vaccines; she took responsibility for public health through her research and legislative proposals in ways that recognized the importance of federal intervention to buttress citizens’ ability to be healthy and independent.

The 12 proposals were:

- Reinsurance of voluntary health insurance plans to encourage carriers to provide better benefits for more people

- Separate matching with the states of public assistance funds to provide medical care for the four groups of public assistance recipients

- Insurance by the federal government of mortgage loans made by private lending institutions for the construction of health facilities

- A five-year program of grants to state vocational education agencies for the training of practical nurses

- A program of traineeships for graduate professional nurses to prepare them for administrative, research and teaching positions and a similar program to provide advanced training for public health specialists, including mental health

- Improvement and expansion of the Children’s Bureau programs providing assistance to the states in maintaining service programs for mothers, crippled children and children requiring special health services

- Adoption of a single, unified grants-in-aid structure for public health grants to the states

- Extension and strengthening of the Water Pollution Control Act, together with appropriations to intensify research in both water and air pollution

- Improvements of the status and survivors’ benefits of the Public Health Service Commissioned Corps, one of the country’s seven uniformed services

- An intensified attack on mental illnesses, including increased funds for training of personnel and a new program of grants to the state for mental health projects

- Grants to the states to help them improve their programs and services for juvenile delinquency prevention, diagnosis and treatment

- Increased financial support by the United States for the World Health Organization, a United Nations agency.4

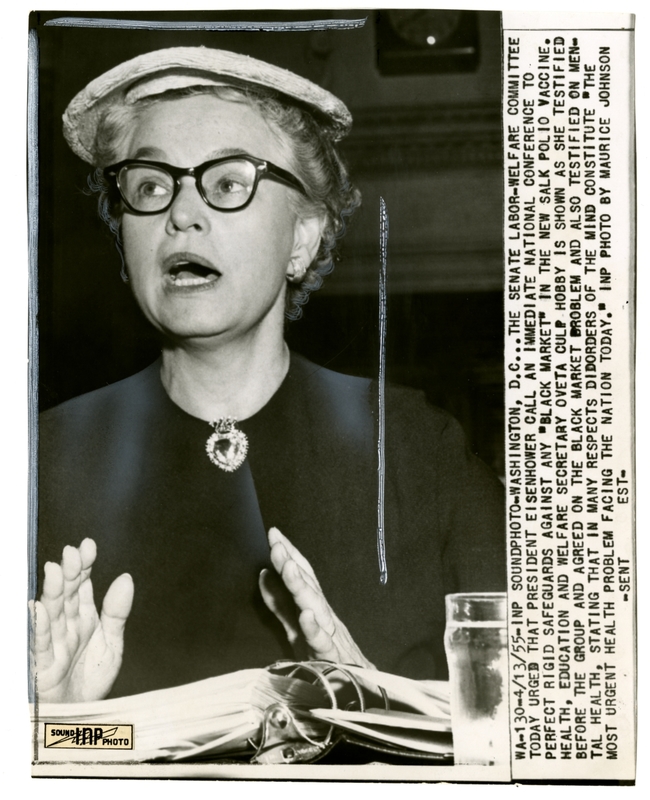

Hobby’s role primarily was to do research on the current state of health in America and propose legislation in service of the administration’s goals. The reinsurance policy, support for medical research, staff and building support for hospitals, and the Salk vaccine were of special interest to Hobby. As a public health official, Oveta took on the challenge of organizing and administering the vaccine for polio made by Salk. Due to factory error and poor distribution of the vaccine, many people were harmed by faulty vaccines (Figure 2).5 Oveta resigned soon after citing her husband’s health, but historians claim that it was a result of criticism from the tragedy.6