Education Motivations

In Eisenhower’s 1954 State of the Union address, he asked for a national conference on education, stating that “‘youth [ ] is being seriously neglected in a vital respect. The nation as a whole is not preparing teachers or building schools fast enough to keep up with the increase in our population’”.1 Hobby put together this conference originally so that she and her team could identify the needs of schools. She always chose to do research and think about possible solutions before taking action on them. The Eisenhower administration actually had no preconceived ideas for education policy before the conference and research results. The administration believed that “it was elemental that an educated citizenry was a fundamental requirement for self-government”.2 What they mean by self-government was that “the concept that primary responsibility for education and maintenance of the public school system rested with the states and the local communities of the nation was accepted almost universally”.3 The idea of a self-governing people and an educated people were very intertwined with the motivation for local and state responsibility. Hobby believed that “‘the responsibility for education is primarily a local and state responsibility. Where a community can not educate children, there is no denying that there is a national responsibility . . . if we are to perpetuate a self-governing people’”.4 Due to the controversial Brown v. Board decision and pushback from Southern segregationists, the administration further pushed back responsibility to the states and local communities by framing it as the way for “self-governance.”

Hobby and the Eisenhower administration had refused any bills that proposed federal grants for school construction because she believed that “any grants [ ] would deter construction of school buildings rather than stimulate it, since most states and school districts would be encouraged to postpone construction in the hope of getting federal help eventually under the priority system which would be unavoidable”.5 Hobby and her department believed that helping states develop their individual action programs and expanding research activities of the Office of Education would be the best long-term solution.6

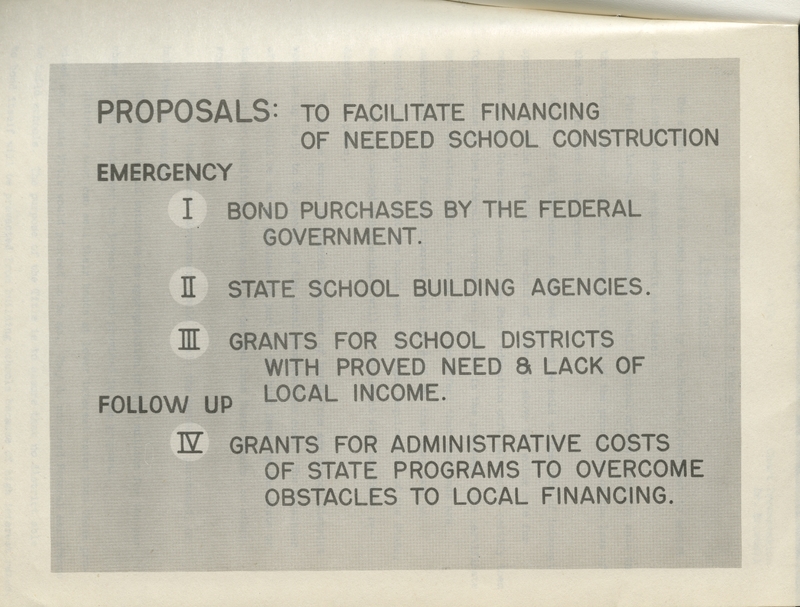

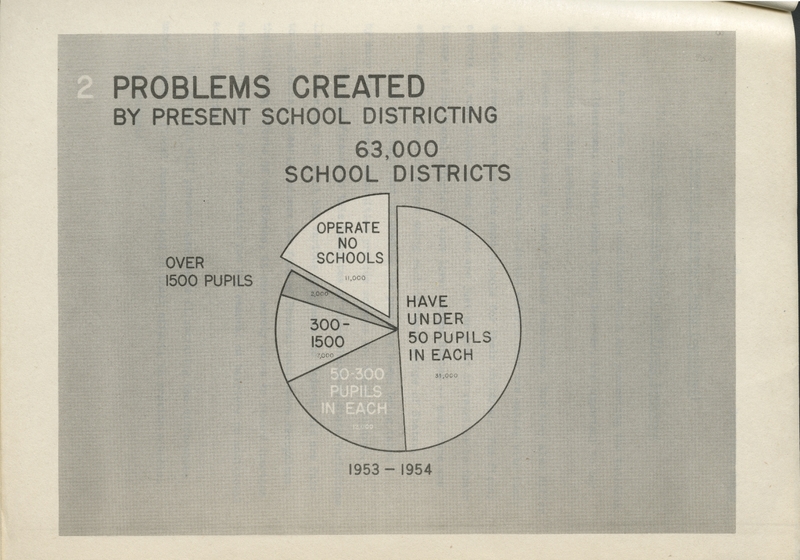

Through research, Hobby identified that there would not be enough schools for the school-age-children (Figure 1, 2). This was due to the steadily growing population of the nation as well as lack of resources during the depression of the 1930s. Later, because of WWII and the Korean War, America did not have the materials necessary for new buildings. However, she did not want to just hand out federal grants to people. Hobby wanted to give a conference on education because she thought it would be faster than giving out federal grants to figure out what the needs of the states and local communities were. This way, she could accurately distribute funds for the states for school construction. Hobby proposed a financing program for federal purchase of school bonds to encourage school construction.

When she took over the Children’s Bureau, the previous leaders of the bureau had already identified juvenile delinquency as a problem for children’s welfare and national welfare. From Hobby’s research, she identified that not much was done about it because of the lack of staffing and national leadership in the Juvenile Delinquency Project of the Children’s Bureau.7 Although Hobby believed that juvenile delinquency problem should also be solved through local communities and government, she recognized that the federal government should take a leadership role in introducing programs and initiatives to train people in controlling and ameliorate the problem of juvenile delinquency. Hobby was also very active in solving the problem of increased juvenile delinquency which she described as a “‘personal and social sickness’” in which a lot of mental health counseling was needed.8