Welfare Motivations

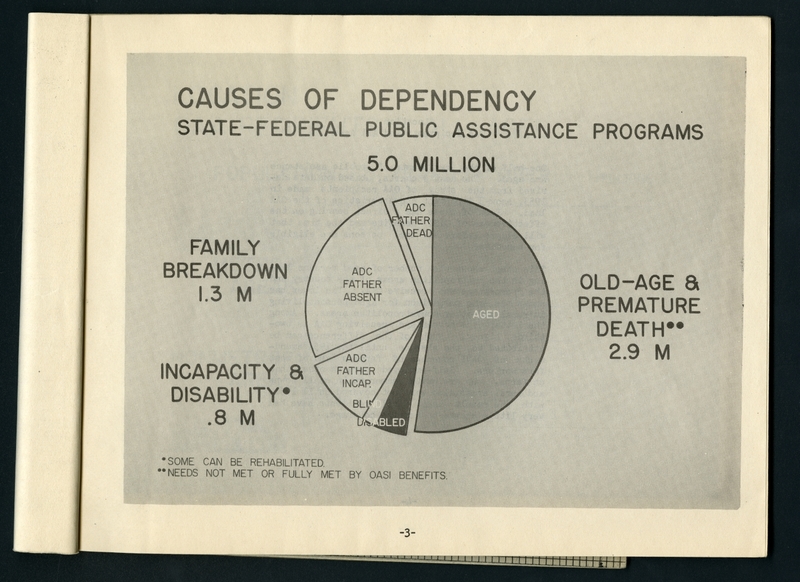

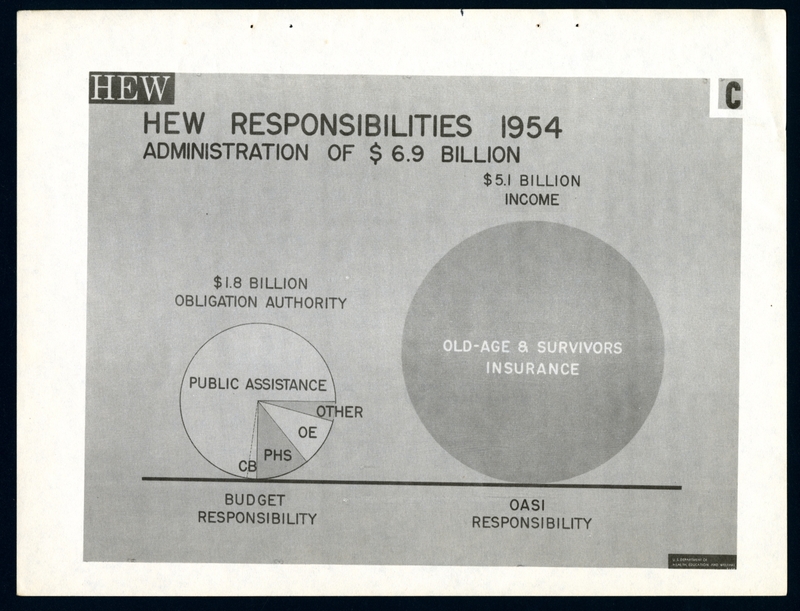

Brian Spinks, an editor from the Houston Post, wrote an unpublished history of the department of health, education, and welfare throughout the years that Hobby was in the position of Secretary. He had been brought to Washington by Hobby because she wanted to influence historical record-keeping of her department so that it was unbiased.1 He recorded the debate over how to approach the issue of social security for the American people as a conflict between those who believed that it was just a welfare program and those who believed that it was a social insurance program. He explains that “the fundamental belief of Americans in the dignity of the individual also was involved in the problem. Public assistance . . . was essentially public relief . . . and it was tainted with humiliation.”2 The opponents of expanding the Social Security Act argued that having the federal government involved would make people dependent and lazy. While Eisenhower and Hobby sympathized with this view, they came to believe that “‘[t]he Social Security system . . . represents the source of security . . . for our economy. It is almost universal in coverage of employment.’”3 The proponents of the expansion of Social Security such as organized labor, organizations for the aged, and socialist partners argued that this security would reduce fear and destitution while giving people more confidence, making them productive members of society. Both Eisenhower and Hobby received copious research from Wilbur Cohen who, through his research and strong commitment to expanding the social insurance program, was able to influence these two “middle way” political figures. As both the President’s and the Secretary’s ideologies shifted from the former to the latter viewpoint on social security, Eisenhower, with the Secretary’s support and research, ended up proposing amendments that were much more liberal than what he had originally put forward in 1952, a modest expansion of the Social Security Act.4 President Eisenhower and Secretary Hobby had very similar political ideologies even as they changed, and both supported each other completely when they worked together.5 In 1954, one of the problems with the Old Age and Survivorship Insurance (OASI) program was that the benefits were too low for adequate living conditions. Eisenhower proposed changes which eventually became amendments to the Social Security Act of 1935 by extending coverage and focusing on “providing economic security for the individual in his old age and for his family (Figure 1, 2).”6 This was a cornerstone of the motivation behind social security policymaking of the original legislation. Thus, one goal was to extend coverage to 10 million people including farmers, doctors, lawyers, and other self-employed professional people, and that goal was met. A “retirement test” which reduced benefits if the beneficiary continued to work was relaxed. This would encourage, not disincentivize, more people over 65 years old to work if they chose. The benefit rights of disabled people would be protected or “frozen” during their period of disability so that an injustice would not be caused by loss of retirement of survivorship rights. Based on these amendments, it was estimated that the aged eligible for the benefits would increase from 45-70%.7 The Social Security program also became closely linked with the Office of Vocational Rehabilitation because there was a provision that disability determinations would be made by state vocational rehabilitation agencies.