Health Motivations

The reinsurance proposal was one that caught the most attention as well as the most controversy in Congress. On reinsurance, Eisenhower believed it to be a virtuous cycle that has a socially beneficial dimension and that “‘the best way for our people to provide themselves the resources to obtain good medical care is to participate in voluntary health insurance plans . . . progress indicates that [ ] voluntary organizations can reach many more people and provide better and broader benefits. They should be encouraged and helped to do so.’”1 Both Eisenhower and Hobby believed that there should be no federal compulsory health insurance. They argued that its “‘crushing cost, wasteful inefficiency, bureaucratic deadweight and debased standards of medical care.’”2 Eisenhower and Hobby did not believe in federal compulsory health insurance and instead believed in the self-sufficiency of Americans to obtain their own medical care by giving federal benefits to health insurance companies.

Hobby did believe that the government should stimulate development of hospital service in local administration and support scientific research because her department’s research showed that these were gaps the federal government should fill (Figure 1). The federal reinsurance program bill was narrowly focused on relieving the limitations and inadequacies of health insurance protection for terrible illnesses, but was still adamantly opposed by the AMA and Chamber of Commerce who believed that it would make citizens too reliant and believe in “socialized medicine.”3 Hobby continually defended Eisenhower’s plan saying that he “‘has consistently urged the acceptance of increased local responsibility, except in matters where the resources of only the federal government are sufficient to assure economical and effective action.’”4 The AMA continually challenged Hobby “to convince the American public that physicians are the sole authority that can properly decide on organization, financing, and regulation of medical care practice.”5 In response, “her staff at the Women’s Army Corps had described Hobby’s frequent reaction when challenged by strong opposition. She would cry ‘Hand me my sword!’ while looking around for files, clipboards, or any other weapons or supplies she might need to meet the challenge. Her reaction to the AMA demonstration of its power was similar.”6

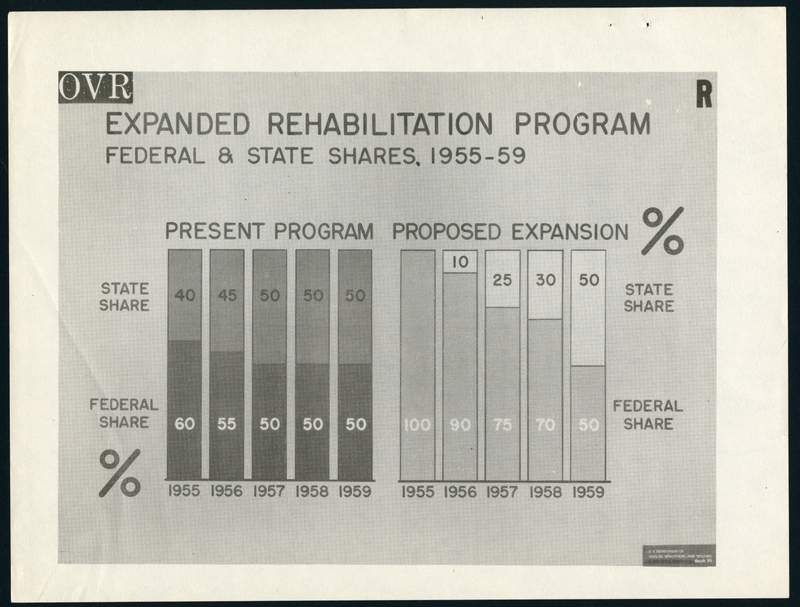

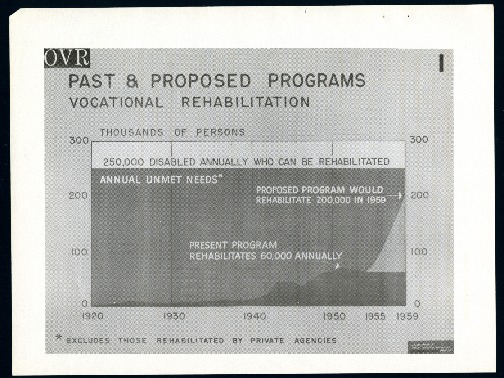

Eisenhower was also a great proponent of medical research and requested expansions of medical research funds year after year. Hobby joined and also requested more funds for the Public Health Service and was able to receive “the best health program yet.”7 However, even as Eisenhower asked for more public assistance programs, both he and Hobby faced walls. He argued that “‘the health of our people is one of our most precious assets . . . Otherwise, we as people are guilty not only of neglect of human suffering but also of wasting our national strength.’”8 Eisenhower argued that expanding hospital construction grants and vocational rehabilitation would go far for Americans’ immediate and future welfare (Figure 2, 3).9 He also argued that more trained personnel were needed to meet growing America’s health needs. Taking an anti-Communist stance, Eisenhower also believed that increasing support for the World Health Organization would keep Communism at bay by alleviating distress and poverty in countries going through economic development.10 Hobby also spoke about the needs of American children: improved health care, better educational opportunities, and combating juvenile delinquency.11 However, she believed that accountability lay first and foremost with parents, followed by communities, then states. Through research, Hobby also found a need for more public health centers and hospitals. The Health Facilities Mortgage Insurance Act of 1954 would try to promote private financing of health facilities and to build and convert structures to be used as hospitals, nursing homes, rehabilitation centers.12 In the case of public funding, Secretary Hobby had taken the position that the role of the federal government was to support state and local communities in improving their services and facilities.13 Thus, she implemented many grant structures that would make states match federal grants given.

In 1953, due to demands of the public and the federal government, many researchers began searching for a vaccine. The distribution and contracting responsibilities were under Hobby because it was considered the worst disease and public health issue in the 1950s. Victims of the disease were also often children and young adults.14 In the race for a vaccine, Jonas Salk’s method was chosen, but large-scale vaccine manufacturing was not available to produce enough for demand. Coming from Houston where the people trusted the health care system a lot, Hobby did not expect the pressure in demand and production. Hobby explained her method of distributing the vaccine in that she “‘set up a regional system of distribution to be sure that vaccine we had was apportioned fairly . . . we made funds available really in the public health and public welfare for people who could not afford it. We originated the vaccine distribution program.’”15 Hobby and the Eisenhower administration argued that free vaccines would set a dangerous precedent and wanted to wait for state action.16