Health Implementations

In order to increase benefits and coverage, Eisenhower proposed to establish a separate reinsurance service inside of HEW for private and nonprofit carriers.1 Besides Hobby’s role as a support of Eisenhower’s proposals, she also led the department in conducting research on health insurance. It was found that in 1952, about 24 million people had family incomes less than $2,000 a year and could not afford voluntary health insurance, and 12% of the population only had hospitalization insurance. Only 3% had comprehensive health insurance. To help with all of these studies, Hobby appointed a National Advisory Council on Health Service Prepayment Plans.2 A reinsurance fund of $25 million in credit from the Treasury was also established in which the secretary would have some authority over premiums that carriers could charge.

To implement many of the proposals that Eisenhower put forward in 1954, Hobby asked for $125 million for hospital and health facility construction grants in 1955-1956. She asked for $89 million for the National Institutes of Health to increase federally-funded health research. Although Hobby also asked for water pollution control research funds from Congress as well, the House cut funding and also cut funds that tried to expand vocational rehabilitation grants. In the end, the 1955-1956 fiscal year gave the Public Health Service $323.5 million and additional funds for providing poliomyelitis vaccinations.3 Congress authorized $182 million to expand federal-state-local hospital building and $150 million to build more chronic disease hospitals for medical rehabilitation.4

For the juvenile delinquency program in the Children’s Bureau, Hobby first compiled experiences of local, state, and federal agencies and recommendations for improvement.5 New grant structures were proposed in which each state would get a flat rate and could apply for more grants from the federal government to improve their juvenile delinquency control programs. The states would also have to match federal funds for programs in the Children’s Bureau. Using the allocated funds for the Water Pollution Control Act, Hobby and her team eventually set up a research laboratory in Cincinnati to study the purification and waste treatments and how they affected surrounding populations. Besides research, consultation services for states were also set up as well as federal assistance programs to deal with interstate waste.6 On training health personnel, Hobby thought that the best resolution was to support the professional nurses with practical nurses. She advocated setting up programs that would train practical nurses.7 In 1954, mental health programs would also be a target of public health grants. In 1955, bills that were passed included a mental health study bill, air pollution research bill, free poliomyelitis vaccinations for children and mothers unable to pay, and increased contributions to the WHO (Figure 1).

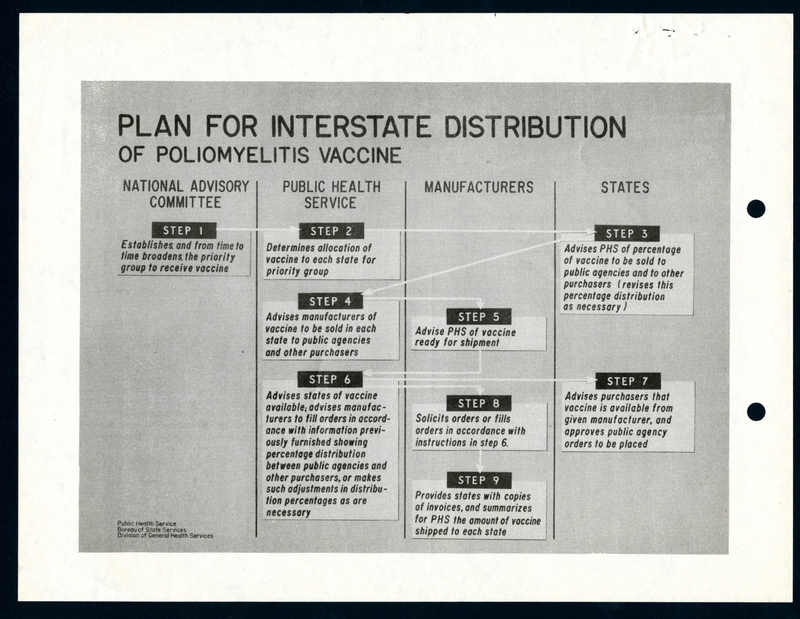

On the polio vaccination, Hobby had written Salk many times on his work with the vaccine. In 1953, Salk worked a vaccine for 7,000 children that had no adverse effects.8 Hobby immediately pushed for large scale testing of the newly developed vaccine. However, lab results were not available until right before the 1955 polio season, so there was not enough time to produce millions of vaccines. Basil O’Connor of the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis placed orders with six pharmaceuticals to make 27 doses of Salk vaccine to make the vaccine available and free for first and second grade children. However, he did not wait for HEW’s approval and large scale analysis to finish. Hobby signed license documents for the vaccine after the large scale analysis approved of the vaccine, but HEW had no plans for distribution of the vaccine until Hobby quickly drafted one for regional distribution (Figure 2). Unfortunately, the demand and hysteria grew so high for the vaccine that manufacturers lost control of unshipped inventory which ended up on the black market. The tragedy was that Cutter Laboratories, one of the companies producing the vaccine had taken production shortcuts and caused 26 cases of paralytic polio among children.9 These incidents completely ruined Hobby’s reputation. The Surgeon General, Dr. Scheele, who had urged for faster distribution and had closely worked with Hobby on polio vaccine distribution, resigned. Other HEW staff officials resigned after these incidents as well. Hobby resigned soon after as well, citing her husband’s health as her reason.10