Dowling's Statue

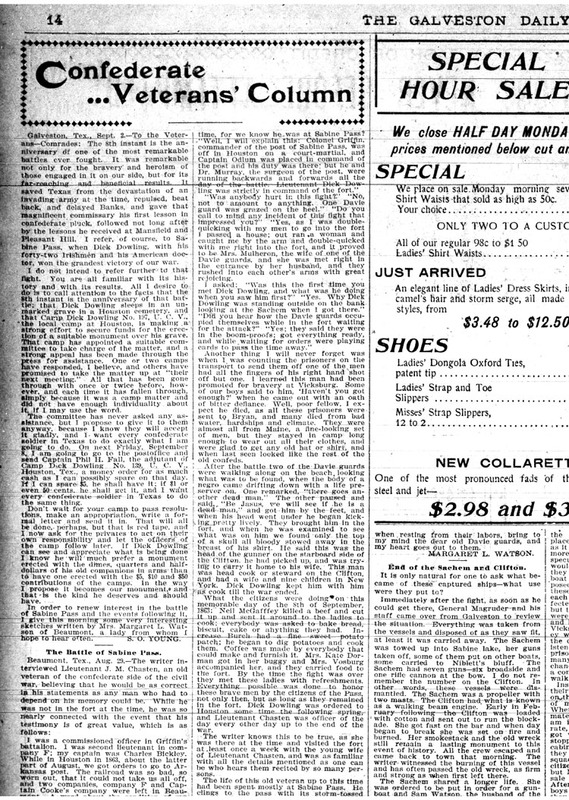

For half a century, the story of Sabine Pass formed the core of Dowling's memory in the Houston area and beyond. Indeed, the tale of the Davis Guard’s victory over overwhelming odds was retold as far away as San Francisco, where an article recounting the battle was published in 1911 (Item 497). But until the 1890s, little was done to publicly commemorate Dowling or the Davis Guards in the public spaces of Houston. This changed around the turn of the century as a new wave of public art and commemoration about the Confedarcy and the Civil War more generally swept throughout the United States.

The Civil War marked major changes in the way the public remembered the average solider. Cemeteries became not only planned places of mourning, but also public meeting places. Former soldiers also worked hard preserving former battlefields, turning them into privately sponsored parks. By the end of the nineteenth century, the erection of statues and memorials about the Civil War also accelerated all over the county, but particularly in the South. Between the years of 1863 to 1879 Connecticut had built 32 statues honoring soldiers, while Virginia constructed only 10. In a few decades, however, things had changed. Between 1900 and 1919 Connecticut built 34 monuments while Virginia built a whopping 83. Statues were often sponsored by the United Confederate Veterans (UCV) and by the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC), two organizations dedicated to preserving a memory of the Civil War that favored Southern interpretations about the causes and character of the conflict. In many Southern cities, groups like the UCV and the UDC also began trying to preserve their stories about the Civil War by altering the physical landscape itself with statues, memorials, parks, and other public spaces dedicated to Confederates and their stories.

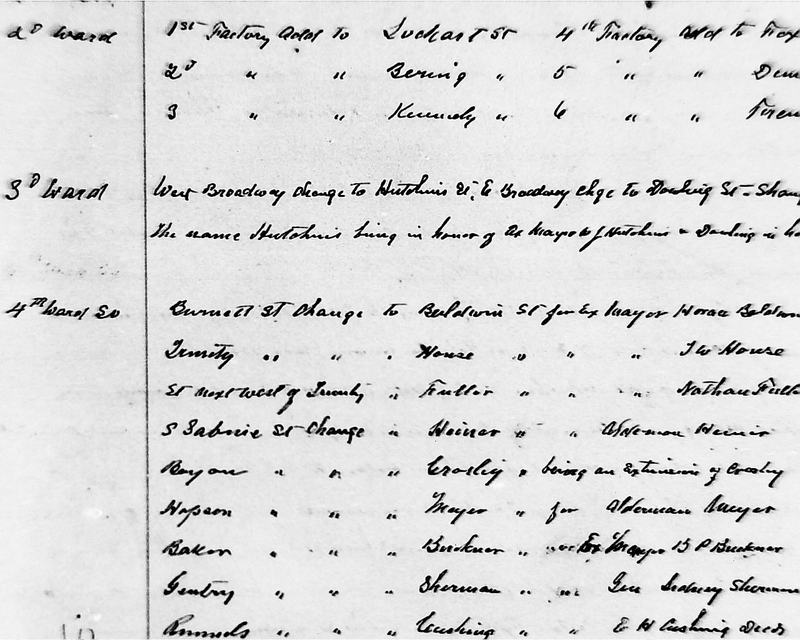

Dowling, too, began to move out of printed stories and into public spaces during the 1880s and 1890s. In 1889, Dick Dowling’s daughter received a gold medal at a ceremony in the Texas State House of Representatives "as a token of esteem for her distinguished father and as an expression of their appreciation of the services he rendered the 'Lost Cause', and especially the people of Texas in saving their State from invasion in 1863 by the Federal Army" (Item 780). Only a few years later in Houston, the name of East Broadway was changed to Dowling Street "in honor of Dick Dowling, the hero of Sabine Pass" (Item 541). The new Dowling Street intersected the already named Tuam Street, which referred to Dowling’s birthplace in Ireland.

These attempts to honor Dick Dowling and his men with physical markers and public ceremonies coincided with the creation of the United Confederate Veterans (UCV) in 1889. The UCV rapidly gained membership and popularity, creating its own publication, the Confederate Veteran, in January 1893. A UCV Reunion hosted in Houston in May 1895 drew more than 10,000 people for a three-day event, which included speeches by veterans and an appearance by Jefferson Davis's daughter, Winnie. (Click here to read more about this event.) In Houston, a chapter of the UCV created in July 1892 was also named in honor of Lieutenant Dowling, and, in subsequent years, the Dick Dowling Camp attempted to revive public commemoration of its namesake. For example, the Camp was formally presented with a sword said to belong to Dick Dowling on December 5, 1900 in the presence of one of the few surviving members of the Davis Guard (Item 482).

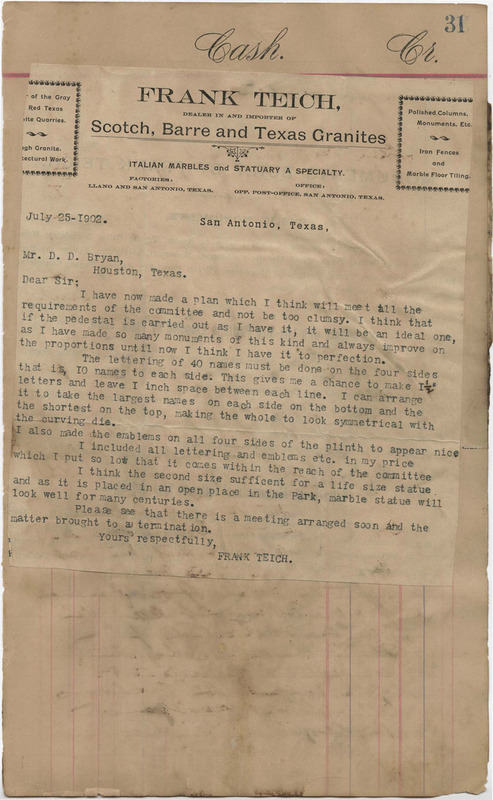

The revival of local interest in Dowling spurred new attempts to construct a stone marker at Dowling's gravesite and to build a marble statue in his honor. Efforts to raise funds for both of these initiatives began in the late 1880s, but turning Dowling's likeness into stone was a hard task. For one thing, building a statue was a costly enterprise. Fundraising for a Dowling monument began first among members of the UCV. But fundraisers ultimately turned to Irish immigrant groups in Houston like the Ancient Order of Hibernians and the Emmett Council to assist with financing and planning the statue. On January 2, 1901, members of these Irish groups joined with UCV supporters to found the Dick Dowling Monument Association, which consolidated fundraising efforts, solicited bids for the construction of a statue, and ultimately hired designer Frank Teich to build a memorial to Dowling and the Davis Guards in Houston.

The involvement of Irish Houstonians in the Monument Association introduced new dimensions to the commemoration of Dowling that had not been emphasized in early versions of his story. Confederate veterans and most white Texans who knew of Dowling focused on Sabine Pass and its relationship to the story of the Confederacy. The Irish, however, wanted not only a figure to honor, but also a way to fit in with the broader community. Emphasizing Dowling's Irish heritage would provide a role model for the entire Irish American community in Houston and also identify the community with Houston as a whole. These unique concerns were reflected in Teich's final design, which was different in several ways from the standard Civil War monument built in this period. Like other statues, the Dowling monument depicted a proud, independent solider. He is not, however, dressed in full regalia or arms. Instead, Dowling, holding a pair of binoculars, rests on his sword, deemphasizing his role in the military. Meanwhile, though many Civil War monuments featured inscriptions explaining the reasons why soldiers fought or the tragic odds they faced, the Dowling statue instead provided a simple list of those who fought in the Davis Guard, together with a list of the organizations that helped build it. Finally, as a testament to the involvement of Irish groups, shamrocks were etched right beside the list of names.

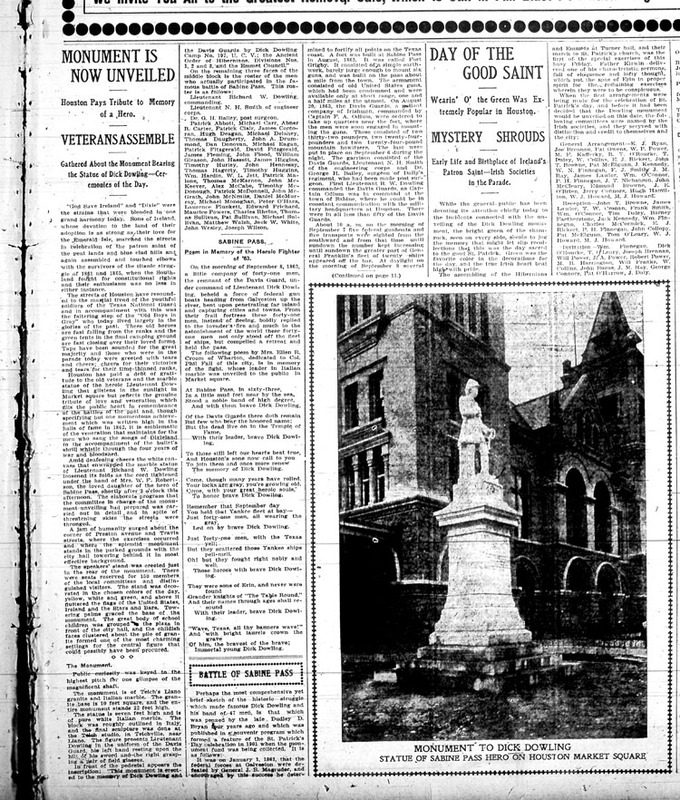

The statue was finally unveiled on March 17, 1905, with a series of ceremonies that reflected the mixture of Irish and Confederate themes. Monument planners had initially hoped to unveil the statue on Jefferson Davis's birthday in 1903. The unveiling, however, was delayed nearly two years to Saint Patrick's Day 1905, a testament to the importance of Irish groups' assistance in bringing the project to completion. The statue's unveiling got considerable attention from the Houston community, as a "jam of humanity" flooded the streets for the dedication ceremony. A parade was held leading to city hall. Surviving members of the Davis Guard attended, along with the Sons of Erin, a local Irish group. The celebration reserved 150 seats for members of local committees and distinguished guests, including Dowling's descendents and the governor of Texas. Mayor of Houston Andrew L. Jackson delivered a speech on the need to remember and commemorate the sacrifices of Confederate cause as well as Dowling as a great Irishman (Items 454, 455, 469)

Such speeches reflected the increasing prominence of Dowling's Irishness in the stories told about him, but stories about his Confederate victory still remained prominent as well. The placement of the statue outside Houston's City Hall also reflected the continuing power of Civil War memory and the memory of the Confederacy in Texas. For decades to come, Houston's city business would be guarded by a Confederate hero, a fact that, while once consoling or unremarked among white Houstonians, became disquieting as the years passed.

Revised June 17, 2020