Debating Dowling in a Changing Houston

By 1958, the Houston Chronicle speculated that "there probably are only a few Houstonians who have more than a hazy idea about Dick Dowling’s contribution to Texas history" (Item 461). Other evidence also suggests that Dowling was no longer remembered with the same gusto as earlier in the century, except among members of Confederate heritage groups and a few other admirers. An additional 1958 article from the Houston Post announced that the sword that made up a part of the Dowling statue had gone missing for a fifth time (Item 467). While it is impossible to know the intent of the thieves, this incident may suggest, if nothing else, that Dowling might no longer have been the revered war hero of years past. Beginning in the 1960s, Dowling and his statue were periodically catapulted back into the public eye. The broader social and political changes in Houston, however, ensured that all future discussions of Dowling's memory would be accompanied by more debate than before.

Less than a decade later, in the mid-1960s, as Texas and the rest of the country marked the centennial of the American Civil War, the City of Houston was very different from the city in which Dowling's statue first stood. In 1905, the year the statue was unveiled outside City Hall, public spaces in the city were racially segregated and poll taxes and other voting restrictions had reduced the turnout of African American voters in Texas to 2 percent. As an example of the pervasive nature of racial sepearation in early twentieth century Houston, one of the few public parks in which African Americans could legally assemble was Emancipation Park, which was bounded by Dowling and Tuam Streets—a telling symbol of how the freedoms of Houston's African American community remained circumscribed for decades after emancipation.

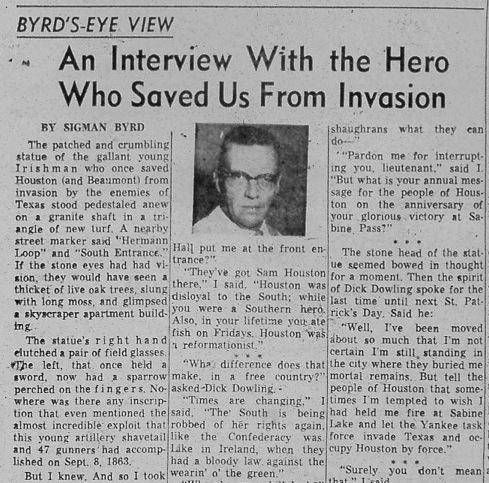

Sixty years after the statue's unveiling, the Civil Rights Movement and school desegregation were changing Houston and African Americans were mobilizing new efforts to challenge racial injustice in the city and beyond. In 1965, for example, African Americans in Houston's Third Ward organized a "Century of Emancipation March and Parade." The parade, which ended at a local bank owned by African Americans, also served as a "symbol that we have awakened to our economic plight and intend to do something tangible" about it (Item 542). Also symbolic was that the march proceeded down Dowling Street, which, despite being named after the Confederate hero, had become a cultural center for Houston's African American community. Dowling Street's musical venues hosted prominent rhythm and blues musicians like Ray Charles. By 1970, the People's Party II, a black nationalist organization modeled after the Black Panthers, had opened a local office on the street.

Concurrently, local historical groups, such as the the Harris County Historical Survey Committee, along with Confederate heritage groups, namely the United Daughters of the Confederacy, continued to promote a heroic image of Dowling. In 1966, Dowling's admirers sponsored a ceremony to mark the erection of a metal tablet from the Texas State Historical Survey Committee near his statue (Item 513). The historic marker (which is no longer extant) gave a brief mention that Dowling was born in Ireland, and members of the Irish heritage group the Ancient Order of Hibernians were present at the ceremony. But the text of the tablet focused almost exclusively on Dowling's story as the leader in a "victory unparalleled in world history" and praised the lieutenant for turning back "15,000" soldiers who had come to "invade" Texas. These exaggerated descriptions of the Battle of Sabine Pass were a reproduction of the "Lost Cause" narratives about Dowling told by Confederates and Confederate veterans one hundred years prior, starting as early as the conclusion of the Civil War.

The placement of a marker at Dowling's statue sprung partly from the increased public attention to the Civil War in the 1960s, but it also symbolized the continued conservatism of a state and city whose officials were resistant to federal Civil Rights legislation and court orders. As one of the largest segregated school systems in the nation in the 1950s, the Houston Independent School District initially responded slowly to the Supreme Court's 1954 ruling against segregation in Brown v. Board of Education. The district did not truly begin to integrate schools until 1970, when a federal judge ordered the district to integrate more rapidly. In the meantime, the struggle over school desegregation coincided with the naming of new schools after Confederate figures. In 1959, HISD opened a new middle school named after Confederate general Albert Sidney Johnson, which was followed in 1962 by the opening of a high school named after Robert E. Lee. (Click here for more about the names of Houston schools.)

In the fall of 1968, less than six months after the assassination of Civil Rights leader Martin Luther King Jr., the Houston Independent School District also opened Richard W. "Dick" Dowling Middle School on the southside of Houston. Dowling joined other, older schools in the city named after Confederate leaders, including Jefferson Davis High School and Jackson Middle School (named after Stonewall Jackson). But this latest decision by the predominantly conservative school board to name a new school after a Confederate symbolized both the subtle and overt resistance of many Houstonians to the growing gains of the Civil Rights movement, like court-ordered school desegregation and the election of Houstonian Barbara Jordan as the first African American to serve in the state legislature since Reconstruction, two years before Dowling Middle School opened its doors (Items 509, 510, and 511).

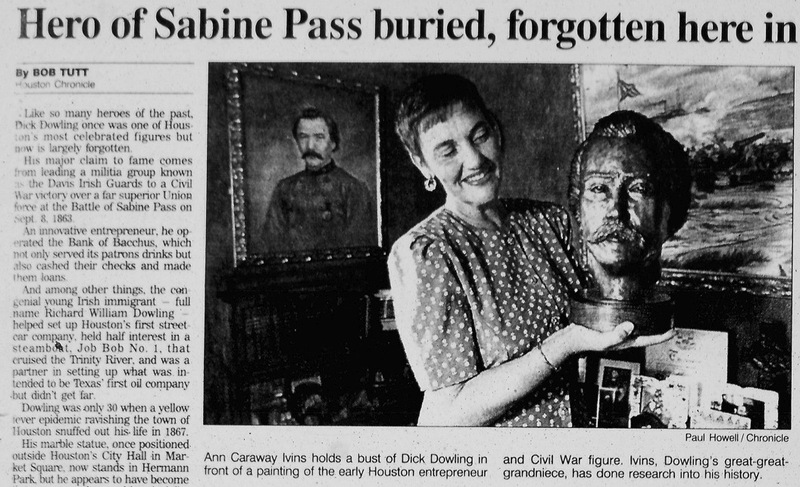

Through these changes, the Dowling statue remained a permanent fixture on the corner of Hermann Park, but attention to it dwindled further in the 1970s and 1980s. Physical care of the statue fell to Larry Miggins, a private citizen and member of the Ancient Order of the Hibernians who was interested in Dowling's history as an Irishman rather than his role in the Battle of Sabine Pass. Miggins worked to preserve the statue of Dowling each year on St. Patrick’s Day by cleaning its exterior with his family (Item 472). The activity became a family tradition and started Miggins on a path toward devotion to the memory of Dowling. In 1989, Miggins gained an important ally in Ann Caraway Ivins, a genealogist and direct descendant of Dick Dowling who conducted extensive research about his life in Ireland and Houston. In 1989, Miggins and Ivins together formed the Dick Dowling Irish Heritage Society, which sponsored commemorative events about Dowling and began a campaign to restore the deteriorating monument and replace the historical marker (Item 376).

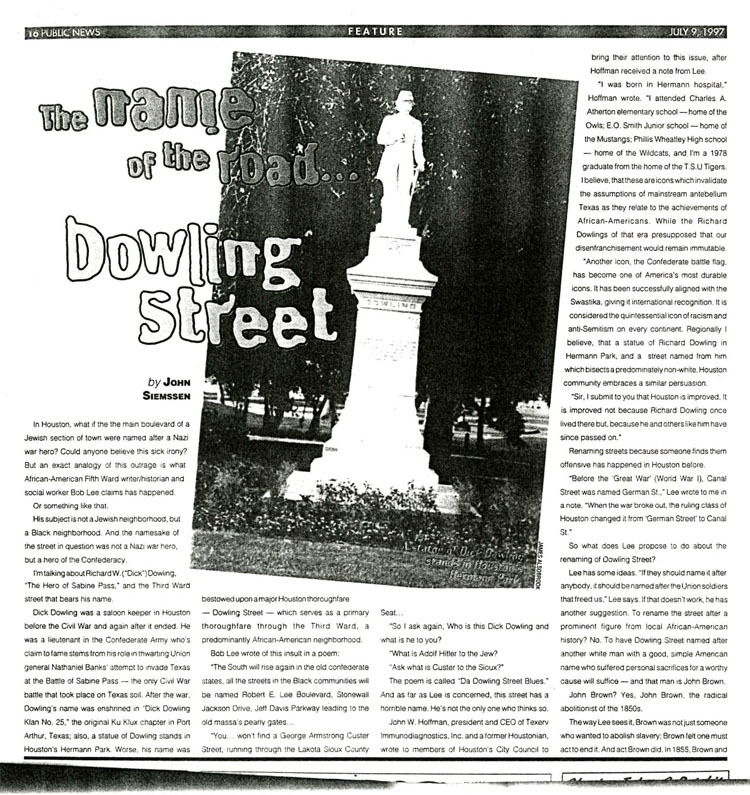

By the 1990s, however, the Dick Dowling Irish Heritage Society faced an uphill battle in its attempts to raise public awareness about Dowling and the statue. A Houston Chronicle article about Ivins had to provide readers with basic information about Dowling, who, by 1997, was "just one more obscure historical figure" (Item 479). In a city no longer dedicated to legal segregation of its schools and public spaces, efforts to recover Dowling's history also sparked more controversy than before. In 1997, while Ivins and other Dowling admirers petitioned the state for a new historical marker at Dowling's statue and made plans for a ceremony to rededicate the site, local African American poet Bob Lee launched a separate effort to change the name of Dowling Street because of the Confederacy's history of enslavement and racial oppression. A poem published by Lee at the time asked "Who is this Dick Dowling and what is he to you? What is Adolf Hitler to the Jew? Ask what is Custer to the Sioux?" (Item 370)

Ivins sought to deflect controversy about Dowling by focusing on his Irish heritage and business ventures, rather than his achievements during the Civil War, and by claiming Dowling's Confederate service was not motivated by racial ideology but instead by a desire to defend his adopted home. By 1997, the decades of dramatic changes in Houston had made it more difficult to call attention to Dowling without confronting Houston's troubled history of slavery and racial segregation.

Revised June 18, 2020