Leaving City Hall

In Houston, attention to Dowling's statue declined gradually after the unveiling of his statue in 1905. In the half century after its dedication, the monument would undergo a series of relocations that would take it from the front of City Hall to a storage shed to an undeveloped corner of Hermann Park. During the same period, some white Houstonians attempted to keep Dowling's story in the public eye, but with decreasing success.

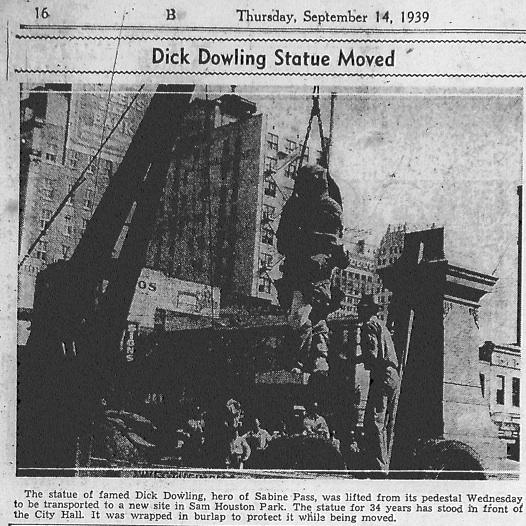

The statue's travels began when it was moved from its location on September 13, 1939. The City of Houston had built a new City Hall and was in the process of repurposing the old building into a bus terminal. Instead of following City Hall to its new location, Dowling's statue was moved to Sam Houston Park, the site of several other historic structures and monuments. Then, in 1957, while renovations on the Noble-Kellum House were taking place, Dowling's statue was placed into storage, its future location undetermined and uncertain (Items 466, 468).

The movement of Dowling's statue into storage upset some white Houstonians who had already complained of a decline in the respect paid to the memory of their hero, specifically at his grave site. As early as 1929, one writer in the Houston Chronicle worried that the lack of a proper marker at Dowling's grave in St. Vincent's Cemetery was an insult to the honor and legacy of Houston's "boy hero." The article lamented that the "neglected mound" of Dowling sinks lower year-by-year, and has become "lost to sight by grass." Author Julia Watts feared that within "a generation" not only would the location of Dowling's grave be lost to sight, but that the memory of Dowling himself would be forgotten without a permanent marker (Item 473).

Local members of the United Confederate Veterans (UCV) and the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) shared these concerns, and between 1929 and 1939, Dowling's admirers worked independently to keep the statue clean and to erect a monument at Dowling's gravesite in 1935. "All Soul's Day" of that year, a Catholic Holy Day that honors the dead, was specifically chosen to pay tribute to Dowling's Irish heritage and Catholic faith. 800 men, women, and children braved "threats of rain" to attend a dedication ceremony at St. Vincent's Cemetery, including several former Confederate veterans, Mayor Oscar Holcombe, Attorney General William McCraw, and Bishop C.E. Byrne of Galveston. Dowling's only living child, "Mrs. Annie Dowling Robertson of Austin," also appeared, reprising the ceremonial role she had played in 1889, when the state legislature honored her father (Item 462).

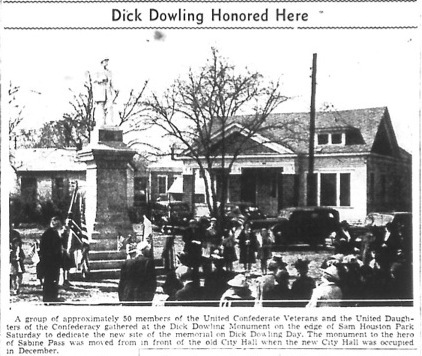

Despite the mayor's attendance at this ceremony, the movement of Dowling's statue to Sam Houston Park only four years later reflected a dwindling of public concern for Dowling's story. Although the UCV and the UDC held ceremonies at the statue's new location in 1940, only about 50 people attended and the mayor, instead of making an appearance, as he had in 1935, dispatched Assistant City Attorney Spurgeon Bell to make "the dedicatory address" in his place (Item 480). Changes in Dowling's notoriety were further signaled both by the statue's movement to storage in 1957 and by a brief dispute over where the statue would be relocated. Initially the City Parks department planned to put the statue on the corner of Fannin Street, in Hermann Park, directly across from Hermann Hospital, both named after Houston philanthropist George H. Hermann. The granite base of Dowling's statue was even placed there temporarily. But when trustees of Hermann's estate objected that this spot had been reserved for a statue of Hermann himself, Dowling's statue was uprooted again in 1958 and moved to the corner of Hermann Park where it stood until 2020 (Item 468). Dowling's statue was removed on June 15th by the City of Houston and moved to an undisclosed location following a few weeks of furor regarding the statues of Confederate war heros. This furor was linked to a series of nationwide protests regarding the racist murder of George Floyd by the police.

After 1958, concern over Dowling's statue would primarily be left to local chapters of the UDC and the Sons of Confederate Veterans, a successor organization to the UCV, and to "unofficial caretaker[s]" like former City Councilman Tom Needham, an Irishman who complained that Dowling's statue had been "shoved in some obscure corner of the park" (Item 468). In the same year Dowling's statue was brought out of storage and placed in that corner, local members of the Sons of Confederate Veterans laid a wreath at the statue on the anniversary of the Battle of Sabine Pass, beginning a tradition of unofficial ceremonies held at the site (Item 536). But the excitement and prestige that had once accompanied public commemoration of Dowling had all but died out. The Chronicle article on the laying of the wreath devoted a single sentence to describing Dowling's victory at Sabine Pass (Item 543). The grandeur and spectacle of public commemoration for Dowling had changed a tremendous amount in the passage of his statue from City Hall through storage and into an "obscure corner" of Hermann Park, where it was watched over by a small and shrinking number of Houstonians.

Click here for a map of all the locations where Dowling's statue has stood since its unveiling.

Revised June 17, 2020