Forced Labor at Sabine Pass

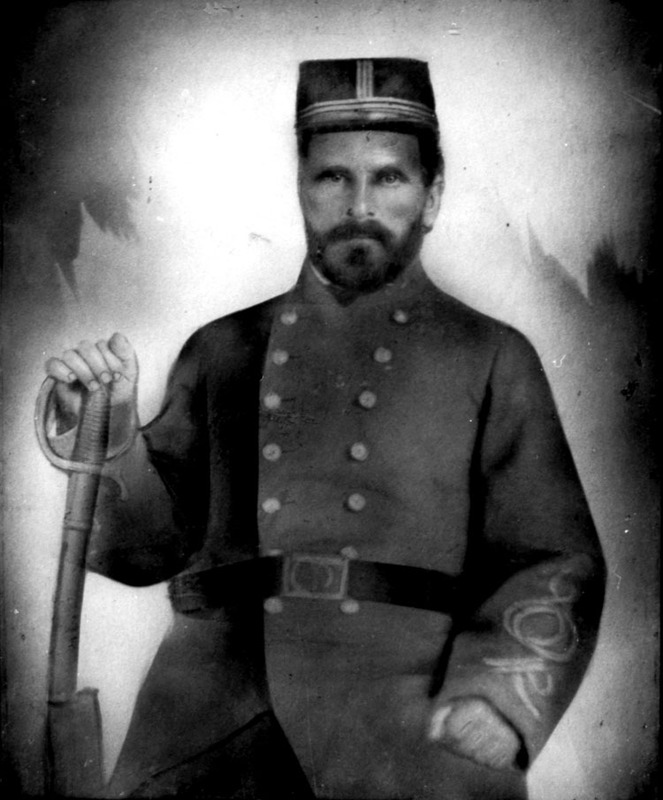

The decision by Confederate officials to make slaves work on military fortifications played a direct role in the Battle of Sabine Pass even prior to the onset of hostilities. Under the policy adopted by Confederate Major General John B. Magruder in 1863, thousands of slaves in Texas were quickly put to work building fortifications in Galveston and on the Texas coastline. Additionally, enslaved labor was used to build Fort Griffin, the small but well-designed fort that Dick Dowling and the Davis Guards later defended in the Battle of Sabine Pass.

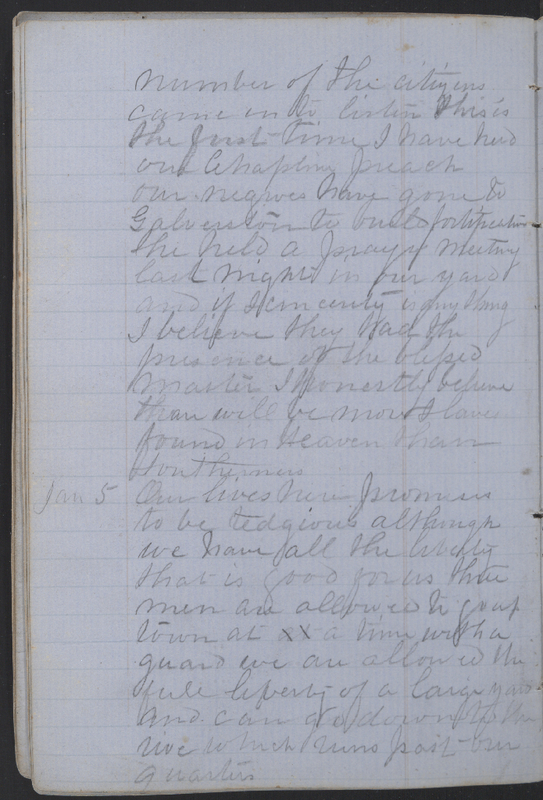

Contemporary evidence shows that slaves were put to work on coastal fortifications throughout 1863. As early as January 4, Alexander Hobbs, a Union private captured at the Battle of Galveston aboard the U.S.S. Harriet Lane, wrote from a Houston prison that "our negroes" (which likely refers to the enslaved people who had been cooking for him and his fellow prisoners since their capture) were being sent to Galveston to work on fortifications. In his diary, Hobbs noted a prayer meeting held by the slaves in the prison yard before they departed (Item 692).

Later that year, enslaved laborers were also sent to work on Fort Griffin, the structure that Dowling would defend in the Battle of Sabine Pass. Years after the battle, Jefferson Davis described the fort that Dowling defended as nothing but a small "mud fort." But, in reality, the batteries built at Sabine Pass in the summer of 1863 were reinforced by wood, iron, and design that modeled the fort according to the latest European ideals for defensive entrenchments. Fort Griffin's location, design, and low profile proved essential to Dowling's victory by allowing his men to concentrate their fire on enemy gunboats while simultaneously protecting themselves from Union cannon fire.

Some information about the enslaved laborers used to build Dowling's batteris can be found in the writings of the Swiss-born Confederate engineer Julius Getulius Kellersberger, who oversaw the construction of Fort Griffin. In a memoir published in German after the war, Kellersberger reported that there were numerous "negroes at our disposal" who performed the hard manual labor that the army required (Item 523). According to Kellersberger's account, about 500 enslaved laborers were brought to Sabine Pass in the summer of 1863. They performed a variety of dangerous jobs, including mounting heavy cannons. Slaves performing the similar work in Galveston suffered high fatality rates. Additionally, those working at Sabine Pass had to work in the August heat and swarms of coastal mosquitoes. As historian Edward T. Cotham reported in his book on the Battle of Sabine Pass, one white engineer who supervised the work wrote from Sabine Pass that "this place is hell." (Check the Further Reading page for information on Cotham's book).

Kellersberger also recalled that enslaved laborers who worked at Fort Griffin were accompanied by the "necessary overseers," whose job on most Southern plantations was to ensure that the enslaved remained at work. Like the slaves who worked on Texas's plantations or were hired out in its cities, the slaves who labored at Fort Griffin were forced to do so. As Cotham also discovered, wartime letters written by Kellersberger to his superior officers reported that the conditions in which they lived and worked were poor. Although enslaved laborers "work hard," Kellersberger reported, they were insufficiently clothed and received inferior rations, a situation that the engineer wished to correct as a matter of "policy." If slaves suffered malnourishment, he reasoned, it would make it difficult to "get any more of them" from slaveholders already unhappy about Magruder's military impressment policies.

After the Battle of Sabine Pass, virtually all commentators on the battle neglected to mention the work that African American laborers were forced to perform at the site. For decades, admirers of Dick Dowling praised him for holding Fort Griffin with fewer than fifty men and argued at length about the precise number of white soldiers who were in the fort when Union ships were turned away. With the exception of Kellersberger, however, these postwar writers did not mention that five hundred slaves had built Dowling's fort. Their experiences therefore remained largely absent from the written record until a distant descendant of Kellersberger discovered his memoir in an attic and deposited her own translation of it in a few Texas libraries, including Fondren Library at Rice University.

Because of such scarce documentation, very little is known today about the African American men who labored at Sabine Pass in the summer of 1863, such as whether any were brought from Houston like the men whom Hobbs witnessed being taken to Galveston in January. But the Confederate Army's use of hundreds of enslaved laborers to build the fort that Dowling defended illustrates clearly the contrasting social systems at war in 1863. While the Union army and navy were serving as agents of emancipation in many of the war's theaters and often sheltered "contrabands" who fled for Union lines, Confederate Texans continue to exploit the labor of slaves in war as they had in peace.

Revised June 19, 2020