From Slaves to Sailors

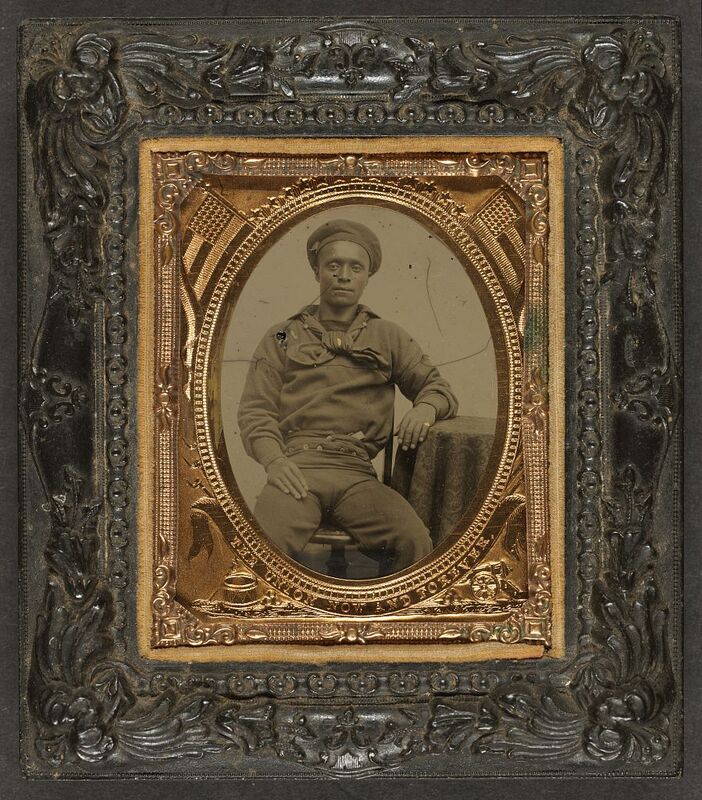

While Confederate Texans built fortifications along the coast in 1863, federal policies were dramatically transforming the relationship between men of color and the United States Army and Navy. The Union Navy began to employ African American men on board ships as crew members and sailors very early in the war. And as the war progressed, blockading squadrons and naval vessels also took on board numerous "contraband" slaves who managed to escape from land to sea. By 1863, the Union navy was enlisting and actively recruiting runaway slaves as crewmembers or paid sailors, usually at the low rank of "landsman." By the end of the war nearly 20,000 black sailors had enlisted, a figure which represented nearly 20 percent of the navy's enlisted men. The majority of these black sailors were men who had been enslaved but seized naval service as a route to freedom.

A few of the thousands of "contraband" slaves who became sailors were present at the battles of Galveston and Sabine Pass in 1863. Both battles demonstrated the unique dangers that African American men faced when they participated in combat operations against the Confederacy. One "escaped slave" participated in the Battle of Galveston of January 1, 1863, before being captured and marched to Houston, and according to a newspaper report at the time, the crowds who gathered in the city to watch the parade of federal prisoners from the U.S.S. Harriet Lane down Main Street jeered at and paid special attention to one of the "negroes" who was "clothed in sailor's uniform" (Item 489).

African American men who became Union sailors risked more than just ridicule if they were captured by Confederate forces. The diary of Union prisoner of war Alexander Hobbs, who was also captured from the U.S.S. Harriet Lane, reported on January 15, 1863, that "six coulered men" from aboard his ship—all "but one or two...free born"—were to be "sold togather" (Item 694). Contemporary records show that "six Negroes claiming to be free" from aboard the Harriet Lane were in fact forced into labor at the Texas State Penitentiary in Huntsville, confirming the outlines of Hobbs's story. Whether they ever escaped the penitentiary, even after war's end, is difficult to tell, and part of a wider pattern of continued enslavement for African Americans across America through progams of convict leasing. (Click here for a letter explaining the fate of these men).

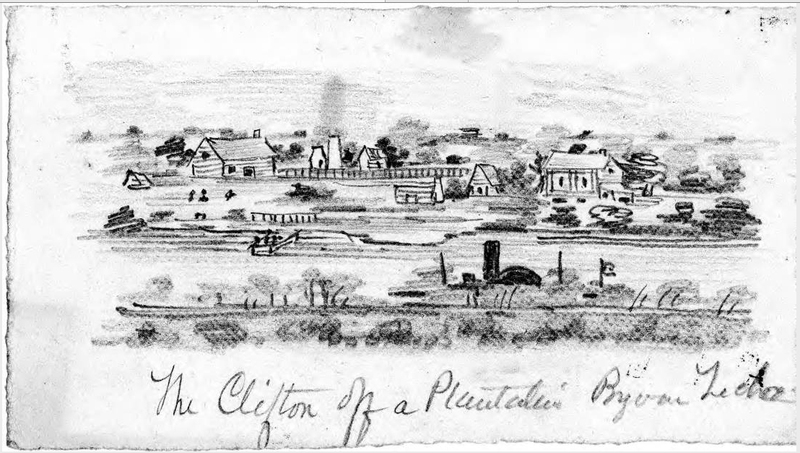

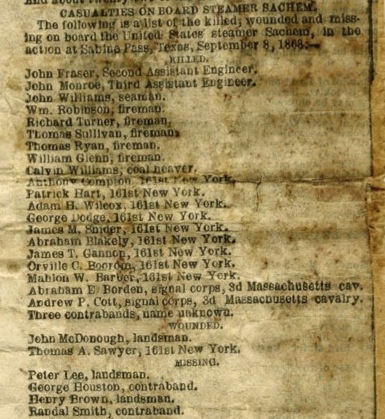

Eight months later, at least two dozen African American sailors were on board the Union gunboats that steamed into Sabine Pass to face Dowling's Davis Guards at Fort Griffin. But many of them never left the Pass again. Casualty reports indicate that several African Americans were among the many Union sailors who suffered gruesome and often fatal wounds when the boiler of the steamship U.S.S. Sachem exploded, spraying scalding hot water on the boat's crew. Many years later a Confederate veteran of the battle vividly remembered a wounded black man who was covered with flour after the battle to treat severe burns to his skin (Item 539). Among those killed at the Battle, according to the surgeon aboard the U.S.S. Clifton, were also "three contrabands"—a term that many Northerners used to describe Southern slaves who escaped to Union lines during the Civil War. And an official casualty list prepared by the commander of the U.S.S. Clifton, Frederick Crocker, also reported the death of "a negro contraband, name unknown" (Items 768, 773).

Little is known about these anonymous men or their origins. But they had probably been held by slaveholders somewhere along the Gulf Coast or in Louisiana before managing to reach the Union naval vessels that sailed into Sabine Pass in September 1863. One white Union Marine assigned to the Clifton and captured by Dowling's men left behind a diary describing frequent encounters between the ship and runaway slaves in Louisiana who were brought aboard as "contraband." But however the story of their movement from slavery to freedom began, it ended in the battle that made Dick Dowling's name famous.

Two other African American men who had once been slaves managed to survive the battle. Their names, though less famous than Dowling's, were even recorded at the time. The captured surgeon of the Clifton listed "George Houston, contraband" and "Randal Smith, contraband" as two members of the crew of the Sachem who were "missing" after the battle. Smith and Houston appear to have been presumed dead by the acting commander of the Sachem, who was also captured after the battle and spent the next eighteen months in a Texas prison (Item 772). But other evidence indicates that Smith and Houston (sometimes spelled Horton or Hurton in casualty reports that were compiled and published later) somehow managed to escape death (Item 767). During the heat of the battle, these two men, and possibly others, swam or splashed across the Pass to seek shelter in the U.S.S. Arizona, which safely escaped from the channel back to New Orleans. A few months later, in December 1863, a George W. Houston and a Randall Smith were listed as African American sailors on the muster rolls of the Arizona, suggesting that these two former slaves had survived and decided to remain in the Navy. By enlisting, they would have been paid wages of around 10 dollars a month. (Click here and search for "George W. Houston or "Randall Smith" to see their muster records).

Most other black sailors involved in the battle were not so fortunate. According to Crocker, among the sailors on board the Clifton who went missing after the battle were "twenty-one of the crew, names unknown—mostly colored." Some of these were presumed to have drowned in the battle, but their exact fates may never be known (Item 768).

Revised June 19, 2020