Slavery's Frontier

By the time of the Civil War, slavery was a growing institution in Texas, and Confederate Texans, much akin to secessionists in other states, were determined to ensure that slavery survived the conflict. The labor of enslaved men and women was crucial to the economy of the Confederate states, and the enslaved themselves were valuable property. By 1860, there were around 4 million enslaved people in the United States, accounting for about one third of the total population of the slaveholding South. As cotton cultivation expanded in states like Alabama, Louisiana, and Texas in the decades before the war, slavery expanded with it.

At the beginning of the war, the size of Texas's total slave population ranked ninth among the states that comprised the Confederacy. But the number of slaveowners, the number of slaves, and the average price of slaves had all climbed rapidly in the decades since 1835. Enslaved persons made up approximately 30 percent of the state's total population according to the 1860 federal census. In several counties near Houston, including Brazoria, Fort Bend, and Montgomery, the majority of the county's population was enslaved. Even in northern prairie counties around Dallas, where there were fewer slaves in 1860, white residents testified that this was due to high prices for slaves rather than a lack of demand (Item 756).

Thus, in the words of historian Randolph B. Campbell, "Texas was slavery's frontier during the late antebellum period; it held the promise of growth and vitality for years to come." (See further reading for Campbell's works.) By 1860, leading white Texans believed that the state's fertile soil made it well-suited for the expansion of cotton production. Some even advocated the reopening of the African slave trade, which had been banned by the United States Congress since 1808. Average slave prices in Texas doubled between 1850 and 1860, but the state's slave population still grew by 200 percent.

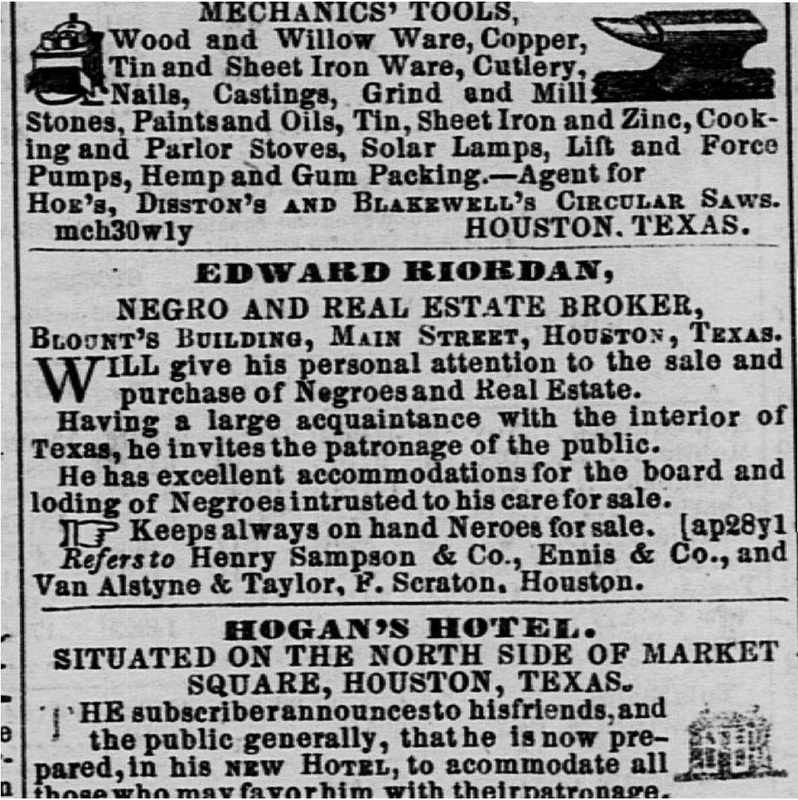

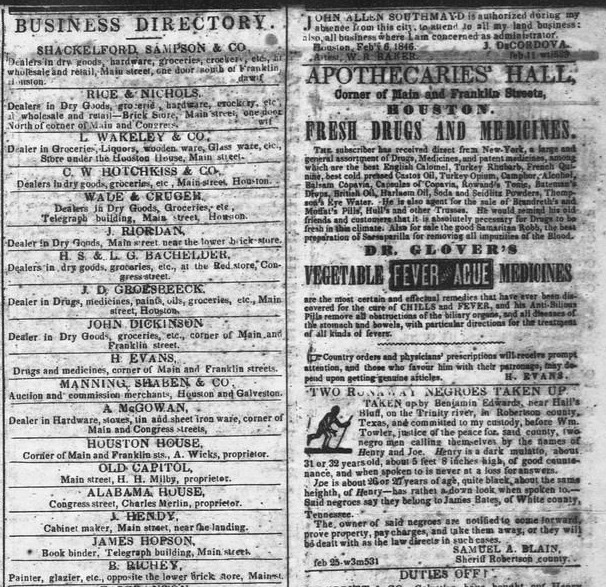

Slavery's growth and vitality was evident on the streets of pre-Civil War Houston, as well. More than 1,000 enslaved persons lived in Harris County. One of the state's wealthy slave traders, Edward H. Riordan, served as a city alderman on the eve of the War and kept his offices and warehouses in Houston near the site of a bar owned by Dick Dowling, the Bank of Bacchus (Item 609). But even Houstonians who did not, like Riordan, buy or sell enslaved people also benefited from the system of slavery. Houston's financial and mercantile community depended on business from the cotton and sugar plantations in surrounding counties where enslaved laborers were numerous. Moreover, white Houstonians who did not legally own slaves could still "hire out" enslaved laborers for a set period of time through paying their legal owners. This practice of the renting of slaves by slaveholders to non-slaveholders increased the number of white Texans who had a vested interest in the institution of slavery.

The prewar history of slavery in Texas helps explain why leading secessionists trumpeted their commitment to the institution early and often. When secessionists gathered in Austin in February 1861 to adopt an ordinance of secession from the Union, secession leaders also issued a declaration of causes that defended racial slavery and proclaimed that it would be a permanent institution in the state. (Click here for the secessionists' declaration.) The following month, secessionists adopted a revised state constitution that explicitly prohibited private citizens or the legislature from emancipating slaves. (Click here for the state constitution of Confederate Texas.) For the remainder of the war, those fighting in Texas for the success of the Confederacy understood that they would be fighting for a state that was firmly committed to the institution of slavery.

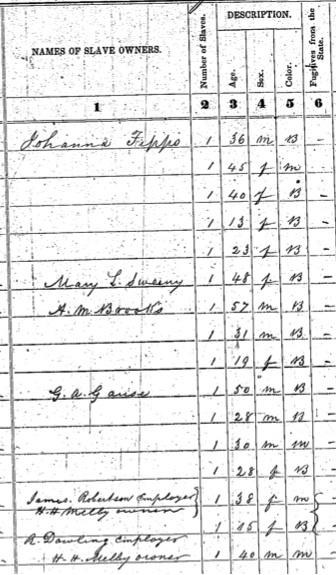

Dick Dowling's early support for the secession movement in Texas suggests that he, too, accepted its stated commitment to slavery, although there is little documentation of Dowling's prewar political views. While there is no evidence that Dowling owned slaves, census records show that he participated in the "hiring" the labor of slaves who were legally owned by others. At least three slaves owned by hotel proprietor H. H. Milby, including a twelve-year-old boy, are listed as being in Dowling's temporary employ in the slave schedule of the 1860 census (Item 819). The work performed by these unnamed men is unknown, but Dowling's use of their labor is strong evidence that he, like other white Texans at the time, did not object to slavery and benefited from it.

Revised June 19, 2020