The Stakes at Sabine Pass

The roles of the enslaved or formerly enslaved in the story of Sabine Pass went mostly unrecorded at the time and were seldom mentioned afterwards by whites on either side of the battle. In the Union, embarrassment over the negligence of the officers who commanded the invasion fleet completely overshadowed the heroism of men like George Houston and Randal Smith who fled slavery, faced Dowling's guns, and survived to join the Union Navy. Confederate victors were more interested in extolling their white hero, Dowling, than in remembering the forced labor that built his fort. For them, and for most historians since, the battle was significant mainly because it prevented the war from spreading into the Texas interior.

At the time, however, slaveholders and slaves understood the high stakes of the Battle of Sabine Pass quite well. Instead of being comforted by Dowling's victory, some slaveholders along the Texas coast were only more anxious about the threat that the Union navy posed, especially since the battle made clear that Union war planners still wanted to capture Texas. On September 27, 1863, after Confederate Acting Brigadier General P. N. Luckett traveled from Houston to present-day Freeport, he reported to his superior that "owing to the heavy planting interest in this section of country, and the precarious tenure by which negro property would be held in case of an invasion," he found "the deepest anxiety" among the area's white inhabitants, who urged him to request that the defenses be strengthened. Fearing that a future Union invasion would be successful, Confederate officials also ordered Getulius Kellersberger to Austin to build new fortifications there. Upon his arrival, Kellersberger was met by another crew of 500 enslaved laborers who had been forced to travel there to perform the work and were "half frozen" because of the winter chill (Item 523).

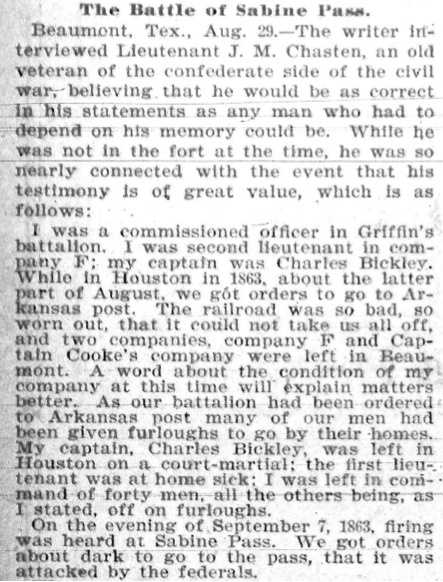

In short, slaveholders in Texas understood how "precarious" their "negro property" would have been if the Union invasion at Sabine Pass had been successful enough to forcibly extend freedom's frontier into the state. Conversely, African American men who fought for the Union army and navy understood how precarious their freedom would be if captured by Confederate forces. Regardless of whether they were "contraband" or free men before the war, Union sailors of color could expect to be counted and treated differently from white prisoners. Following the Battle of Calcasieu Pass on May 17, 1864, for example, a Confederate officer stationed at Sabine Pass reported that of fifteen "Negroes" captured ("7 Northern and 8 Southern"), ten were sent to Houston while the other five were "in [the] charge" of specific Confederate officers or assigned to labor for the Confederacy (Item 771). In 1899, aging Confederate Veteran J. M. Chasten even told an interviewer in Beaumont, Texas, that he remembered capturing "a negro" at the Battle of Sabine Pass who was "the head cook or steward on the Clifton, and had a wife and nine children in New York." According to Chasten, "Dick Dowling kept [the man] with him as cook till the war ended" (Item 539).

No evidence has been found to corroborate Chasten's story, but the memory points to a basic reality about the Battle of Sabine Pass that is only beginning to be understood: at stake in this relatively minor engagement were the same individual and global issues of freedom, labor, race and slavery at stake in the American Civil War as a whole, from New York all the way down south to Houston.