Freedom's Frontier

The 1861 constitutions of Texas and of the wider Confederate States of America were pledged to the permanence of slavery as an institution. By September 1863, however, the Civil War was disrupting the institution in ways that troubled slaveholders and impacted the lives of many slaves living in Louisiana and eastern Texas.

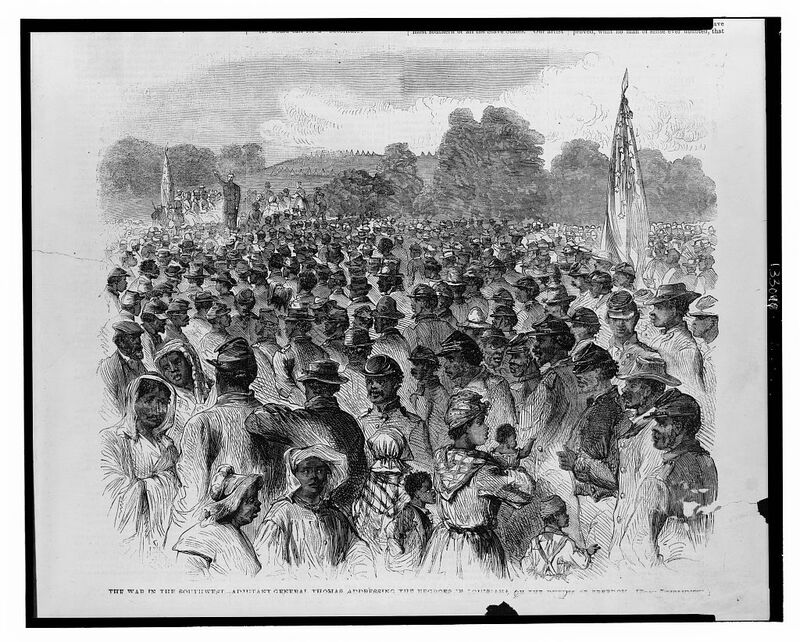

By the time fighting took place in Galveston and Sabine Pass, Union forces were already actively engaged in liberating slaves and employing or enlisting African American men in various parts of the Confederacy, and particularly in nearby Louisiana. As early as 1861, the United States army and navy began treating many enslaved people who escaped to Union camps or boats as "contraband of war" and refused to return them to legal owners. Then, in the summer of 1862, Congress passed the Second Confiscation Act, which in practice extended freedom to all slaves who could reach Union lines. Congress also authorized the military to employ escaping enslaved individuals in various jobs. Finally, on January 1, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, which declared that all slaves in states then in rebellion—including Texas—"are, and henceforward shall be free." The Proclamation also authorized the enlistment of freepeople into "the armed service of the United States."

Throughout the war, hundreds of thousands of Southern slaves seized these new opportunities by flocking to Union camps when they could. They understood the shifting lines of Union forces in the South as a frontier offering freedom to those who could reach it. Many African American men also quickly transformed themselves from legally enslaved persons to "contraband" to paid soldiers and sailors in the Union army and navy, where they directly worked to extend freedom's frontier by participating in combat operations.

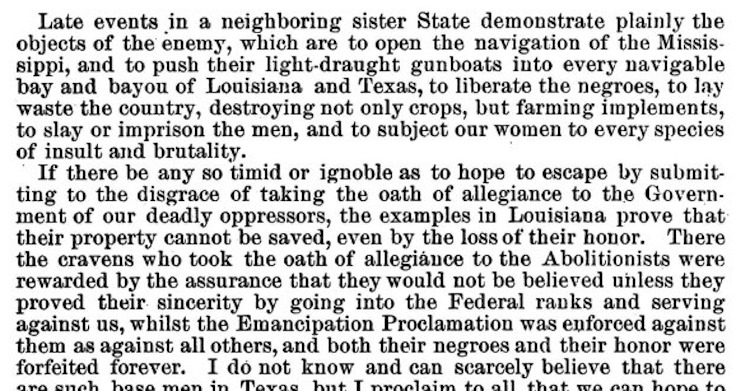

These developments made slaveholders in Texas and neighboring Louisiana worry that their own slaves would soon be freed, especially after 1862 when a large Union force occupied the major port city of New Orleans and the surrounding parishes. The Union expanded its control of the Mississippi Valley with several 1863 campaigns that resulted in the fall of the Mississippi River Fort of Vicksburg in July, splitting the Confederacy in half. In the course of these campaigns, newly enlisted African American soldiers saw combat, demonstrating the impact of the Emancipation Proclamation in the region. Officially, the Proclamation did not apply to those parishes of Louisiana that were under Union occupation as of January 1, 1863, but Union forces who operated outside of these parishes were authorized to liberate slaves. And even within the exempted parishes, some Louisiana planters reported that slaves were aware of Union promises of emancipation and were claiming freedom even where it had not been officially granted. (Click here for a document discussing the effect of wartime emancipation in Louisiana.)

In 1863, many slaveholders in western Louisiana decided to flee with their slaves to Texas instead of risking their slaves freedom, through either Union action or escape. British traveler Arthur Fremantle noted the flight of slaveholders to Texas several times in his journal of the trip when he traveled through eastern Texas, Galveston, and Houston in 1863. (Click here to read Fremantle's narrative.) Meanwhile, because there were no serious military engagements along the Texas coastline until September 1862, when Union forces captured and briefly held Galveston and its port, most slaveholders in coastal Texas had ample time to move their own slaves inland.

The disruption of slavery in Louisiana made clear to Confederate officials and slaveholders in Texas what would happen if Union forces moved inland from Galveston as they had in the Mississippi River valley. Confederate forces thus moved aggressively to recapture Galveston on January 1, 1863 and then began making plans to better fortify the Texas coast in the event of another Union attack by sea.

Building the needed fortifications in Galveston and at Sabine Pass required hard manual labor, and Confederate General John Bankhead Magruder soon found that voluntary labor would not be sufficient to complete the work. Magruder therefore began pressuring slaveholders to send their slaves to do the work, in exchange for hiring fees paid by the Confederate government to slaveowners. According to one proclamation by Magruder, slaveholders who refused to cooperate "would be dealt with strictly under military law" (Item 537). Under this system, between 3,000 and 5,000 enslaved individuals were forced to build new state-of-the-art fortifications in Galveston.

In general, however, slaveholders proved very reluctant to allow the army to use their slaves. Many owners were concerned by the danger military labor posed to the value of their slaves, who might be injured on the job or might use the distance from their owners' homes and proximity to a port as an opportunity to escape. Slaveowners in Texas proved so unwilling to send slaves to support the war effort that Magruder finally had to resort to the impressment of slave labor in the summer of 1863. Under this system, Magruder began taking advantages of a law passed by the Confederate Congress that spring allowing Confederate officers to force slaves to perform military work whether their owners volunteered them or not.

In a letter to the governor of Texas explaining why he had to take this bold new step, Magruder explained that only improved fortifications would prevent the Union from returning to east Texas and invading the state. Slaveholders only had two options, argued Magruder: they could allow the army to use their slaves, or they could lose their slaves to emancipation by invading Union forces. "A mere inspection of the map," said the general, "should satisfy any holder of slave property that these defenses are absolutely necessary to its security" (Item 755).

Revised June 19, 2020